Let's take a minute to appreciate how hard my job is.

I teach writing. It isn't really like most other subjects you study in school.

Take math for instance. On the surface, math seems a lot like writing—you take it almost every year of your education whether you want to or not. Most people either really like it or really hate it. In fact, many students define themselves by whether or not they "get" these subjects: "I'm a numbers person, not a words person," or vice versa, they say.

But math is very different from writing in key ways. Let's discuss three of them.

‘Right and Wrong’ is Wrong

Back up for a sec—I need to clarify something. It’s this:

I don't teach people how to write.

I teach people how to write well, to write more effectively.

You literally learned how to write (that is, how to move a pencil or pen in order to form letters) way back in kindergarten. The basics of putting sentences together were covered not long after. Since then, however, you've had to take a writing class almost every year. Why? Because although you could write, you probably couldn't write in a way that expressed yourself very well.

See, we're already a long way from math. There's essentially no difference between how you add up numbers now and how you did it when you were seven: line up the digits, carry the one, and *bam* you're done. There's not much range between doing addition and doing addition well. Sure there might be different methods (just like some write with their right hand, some with their left, and some type), but aside from right answer versus wrong answer, there's no wiggle room.

In writing, however, there's so much wiggle room. When a teacher asks you to write a paragraph summarizing a chapter you read, there are infinite combinations of words and sentences that you can provide her in response, and every one of them is a fine shade of difference between effective and ineffective. There's a world of difference between "To be, or not to be, that is the question" and "Should I go on living or just end it all now?"

Even worse, the standard is changing all the time. When your second grade teacher asked you to summarize a paragraph, his idea of a great response was probably very different from your college professor's when she asked you to summarize a scholarly article. They each had different ideas of what diction, length, level of detail, focus, and other factors could be considered "effective."

Did you notice that when talking about math I said right and wrong but in talking about writing I subtly shifted to effective and ineffective? That's another problem with writing: there is no right and wrong. Ask a dozen mathematicians what the answer to 7 + 3 is, and you'll almost certainly get a consistent single answer. But ask a dozen writers the best way to, say, decline an invitation to your ex-significant other's wedding, and you'll get a dozen different answers. There is no "best" way—there are only an uncountable number of more and less effective ways.

Case in point: Kate Beaton does a great Hamlet.

So how does this make my job hard? Well for one thing, it's difficult for me to presume to teach you how to do something that you have been doing for well over a decade. Imagine a 12-grade math teacher coming to class the first day and saying, "Alright, I know you think you know addition, but this semester, for the twelfth time in a row, we're gonna drill down and really get to know addition!"°

For another thing, it's quite a trick to teach someone to be better when no one can fully agree on what "better" means. Take the gym teacher who, like me, doesn't teach new skills so much as help students refine long-known skills. Now imagine there's no agreed upon definition of "run faster," "jump higher," or "throw farther." Writing isn't like sports; there's no score, no consistent measurement to decide what's best. Some days I feel like I'm judging a race, but the winner isn't the student who gets to the finish line first but the one who…um…writes the most effective race? And as consistent and clear as I try to be, I know that another writing teacher will probably disagree with my assessment.

Calvin and Hobbes, by Bill Watterson

Linear v. Recursive Learning

Let's look at another difference between math and writing, this time focusing on how they are learned.

Learning Math is Linear

In math, learning tends to be linear. That is, you master an initial concept, which in turns allows you to master the next concept, which allows you to master yet another more complex one. In elementary school you start by learning how to count, then do simple addition, then do simple subtraction, and so on. In high school you master algebra, which unlocks geometry, which unlocks calculus, and so on.

Students may master the concepts at different speeds (I, for instance, took way too long to understand addition and subtraction of negative numbers, which really tanked my seventh grade year), but generally speaking, they master them in the order that's been laid out since time immemorial.

When a student walks into any given math class, the teacher can safely assume that they have a passing understanding of certain concepts—in Algebra II, the teacher need not review the basics of long division or multiplying fractions before he or she launches into factoring and solving equations.

Get it? In math, as in many subjects, learning is roughly linear. Imagine it like a stack of building blocks reaching ever higher, each new block being placed solidly on the one below it. Skip a block and you're building on thin air.°

Learning Writing is Recursive

Learning how to write is anything but linear. You don't just master a concept before moving on to the next one.

Sure, the early basics happen in a linear way. Kindergarteners all learn how to hold a pencil correctly, then they learn how to shape the letters, then they learn to line up the letters into words, leaving space between them. But after that, things get murky. Good writing consists of a large number of interrelated skills like

- spelling

- punctuation

- diction

- paragraphing

- organization

- writing a thesis

- incorporating quotes

- using evidence to back up claims

- anticipating a reader's needs

- citing sources

- logically and clearly moving from point to point

and so many more.

And you don't have to learn any particular one in order to learn another, the way you need to understand order of operations before you can effectively factor an equation. There are plenty of writers out there who are really great at writing a killer thesis and organizing their essays but who can't spell well. There are many who can spell chrysanthemum on the first try, every try,° but who write clunky sentences and paragraphs.

Worse still, no one ever really finishes learning any of these topics. They just get better at them—but the better they get, the more they realize they have to learn.

A nonlinear learning process like this—where concepts can be learned in any order and where the learner moves forward in some ways, hangs back in others, repeats steps, skips steps, and generally futzes around in the dark most of the time—is called recursive.

Photo by beasty . on Unsplash

So how does this make my job hard? Teaching something that must be learned recursively is like building a house—only you have to keep dismantling parts you already built so you can build new parts, then reassemble what you took apart, then move it across the room, then take it apart and put it back together again.

Nature and Nurture

Lastly, let's consider a third way that learning writing and learning math are different. Above, we likened math skills to a set of building blocks that can be stacked in order, but we pointed out that writing skills, which are learned recursively, aren't like blocks.

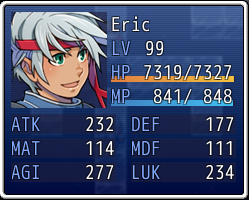

So what are they like? How about this metaphor: your writing skills are less like a stack of building blocks and more like the personal stats of a character in a role-playing game (RPG).° Characters in these games usually have categories such as the following that describe their personal abilities:

- strength

- constitution

- intelligence

- stamina

- charisma

- wisdom

These abilities are interrelated but they are not directly linked; that is, when a character improves in one area it doesn't mean they improve in all other areas by the same amount. Often, characters are predisposed to improving more rapidly in a certain area. For example, a character who is a natural fighter will rapidly increase their strength stats while their intelligence move only incrementally, and vice versa for a more scholarly character.

I sure hope Eric here has enough, um, MDF(?) to pass his classes this semester.

Compare this to yourself as a writer. Some aspects of writing come more easily than others—maybe you're naturally a gifted speller, or you have a poet's touch, or you can look at complex information and implicitly understand the best order to present it to a reader. Other aspects of writing really challenge you—try as you might, you can never remember how a semicolon works, or you struggle to write effective introductions.

We use words like talent to describe those things that come easily. We say "it's in your nature."

Then, of course, there's the nurture side of things. In addition to your natural affinity for some skills over others, by the time you get to a junior-year college writing class (the kind I teach), you've had upwards of 15 years of writing instruction. Teachers along the way have helped you maximize your natural talents and overcome your weaknesses to some degree or another. You've completed hundreds of writing assignments of all types and used writing in your lives in myriad ways: writing for the school newspaper, composing poetry and pop songs, penning love letters, recording your observations in a journal or diary, working on your young adult fantasy novel, etc. etc. etc.

Let's go back to the RPG character metaphor for a minute. You're the protagonist of your game, and you've created a perfectly unique character with completely different stats from anyone else out there playing the game.°

But now imagine life from my perspective. On the first day of class, I have to stand in front of 18 unique writers without any idea of what inborn talents they have and without any clue as to what their middle and high school writing teachers assigned them, what grades they got, what interests them, or what they struggle with.

If my students dressed like this, I'd be better able to guess what nature and nurture had made of them.

If I had just one student, I might be able to get to know that writer well enough to understand his or her nature and nurture and then custom-build a curriculum to help him or her level-up, a process which we've previously defined as recursive, meaning it has no clear path, no definable steps, and no end point.

But I don't have just one student. I have 18. Per class. And I typically teach four classes a semester.

In a word, it's impossible. My job is impossible.

It Gets Worse: The Future

Okay, let's review real quick. So far, I've argued that three elements of writing make my job difficult:

- In writing, there is no consistent definition of "right" and "wrong," so what am I even supposed to teach?

- Writing is learned recursively, in no exact order, so how am I even supposed to teach that?

- Every student has a unique history of recursive learning, of nature and nurture, so how am I even supposed to design a class that works for everyone?

That last point focuses on my students' pasts—but what about their futures? What about how they will each use writing in their own lives after they leave my class?

I mentioned how no one fully agrees on what constitutes right and wrong effective and ineffective writing, that any two people will inevitably have different opinions on what is best.

The most dramatic way we see this in our everyday lives is in how different professions use writing for very different ends and thus value different things. For example,

- Academics use writing (in part) to develop their reputations as intelligent researchers, so they often value big words and long sentences with convoluted structures.

- On the other hand, children's book authors use writing to teach simple concepts and a love of reading, so they value short words and simple sentences spread out over many pages and splashed with vibrant colors.

- Doctors and nurses use writing to track patients' progress and develop treatment plans, so clarity, correctness, and good handwriting are paramount.

- The IRS values not essays but long tax forms and worksheets that allow Americans to report the thousands of ways they make money and qualify for tax exemptions and deductions.

- Business professionals use reports to transmit key information to multiple groups of stakeholders, each with their own interests and needs, so they value writing that employs headings, topic sentences, and a careful control of diction to accommodate that variety of readers.

Name a profession, and you'll have to define what effective and ineffective mean specifically for writing in that field. Choose a specific job within that field, and you have to define those terms even more closely. Name a specific opening for that job, in a specific office, with a specific boss and clients, and…well, you get my point.

So back to my four classrooms, each with 18 idiosyncratic writers. Not only do I not know where these people all came from, but I know that each is going to a different place down the road, where they'll need a different set of skills to succeed. Only I don't know where those places are, so I can't really map out the road to them on my own.

If you'll forgive yet another metaphor: teaching writing is like having a nightmare that you're a traffic cop, standing in the middle of an intersection of dozens of roads. And all at once from every direction come cars, each one trying to get to a different place and none of them knowing the way, each of them expecting me to point out the right road, even though they haven't told me where it is they are headed. And suddenly I see that it isn't just cars and roads—every form of transportation is hurtling towards me, and every type of path is on offer. Helicopters, submarines, tricycles, paper airplanes— they're all trying to find the right highway/shipping lane/alley/bike path/orbit from where it crosses my intersection. Worse still, I barely have time to notice what kind of moving object each is before it takes my instruction of which way to go and zooms by, the unicycle merging onto the freeway, the tugboat taking the subway line. I realize I'm not just a traffic cop but a GPS and a fortune teller all rolled into one.

A Silver Lining?

So that's where we are. Pretty grim.

I can really identify with this guy

But wait a minute.

My job is only impossible if you consider it to be teaching students how to write better. How about we clarify our terms one more time? How about we don't say that

I teach students how to write more effectively.

Instead, let's say that

I create conditions in which students can become better writers.

See, when you get down to it, the most important thing that will happen in my classroom any semester is not that I'll teach—it's that my students will learn. Teaching can never happen unless learning happens, and a teacher cannot exist without students. But, on the other hand, learning can happen without teaching, and students often do just fine without a teacher.

Since the one thing (teaching) is dependent on the other thing (learning), it doesn't make sense to focus on the dependent side of the equation.°

In other words, whether or not I am successful at teaching isn't the crucial thing. The crucial thing is whether or not my students succeed in becoming better writers.

So maybe it was a bad idea to focus this whole essay on me and how hard my job is. Maybe I should've written "On the Near-Impossibility of Learning Writing" instead.

Because it's true: learning to write well is so so so hard, for all the reasons stated above:

- It's very hard for students to understand and articulate what constitutes "good" and "bad" in writing, and the standard is constantly changing dependent on the situation.

- Learning to write is a recursive process that involves an uncounted number of interrelated skills, so it's extremely hard to map out the path ahead and ensure success. It's easy to get frustrated by the sensation that you are getting worse, not better.

- So much of your success is dependent on things outside of your control: your natural talents and affinities as well as the luck of where you were born and where you went to school and who taught you.

- Most students don't have a clear idea of what they'll use writing for in the future, so they aren't even sure what their goal is. Hard to get better if you don't know what "better" means.

Geez. When you put it that way, I feel really bad for you. Your job is basically impossible.

But you're in luck! It turns out that writing teachers, wherever you find them, went through all this impossibility already. They learned how to write well in most situations, and they have made careers out of creating conditions in which students like you can become better writers. One of them (me) even wrote this article and built this website to help freely transfer some of his and others' knowledge to you.

Let's be clear though: No one can teach you to be a better writer. Not in a direct way, at least. No one can force you to learn. No one can understand your entire history and future goals and map out a custom-built path to writing success just for you.

Ultimately, you'll have to do that for yourself.

But you've taken a good first step by coming to Grover's English, and maybe even a better step by enrolling in a writing course at a college or university, a course taught by someone who, like me, is happily living in the impossible nightmare of trying to direct all those trains, planes, and automobiles through this endless intersection.

I hope you get where you're going.