When faced with a text that is difficult to comprehend, many of us make the assumption that the problem is us. We aren't smart enough, we reason. Everyone else understands this text with no difficulty, we imagine. I don't belong in college, we declare.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

The truth is that college presents reading challenges to everyone, regardless of natural talent or the quality of one's previous education. The texts you will be assigned in college with be longer, denser, and more complex than readings you completed before. But they aren't there to weed out the worthy from the worthless. They are there as part of the whole project of college: to develop your skills as a critical thinker.

It's more constructive to think about reading challenges not as a judgment of your quality as a student but instead as a call to action: you'll need to expend more time and energy to complete this reading, and you'll need to be more strategic about how you employ your resources. In other words, you need to be a more active reader, one who deliberately engages with texts in order to ensure understanding.

This reading presents many strategies that you can employ to be a more active reader. Regardless of your natural ability, you'll find some of these strategies helpful—maybe even essential—as you are challenged by college-level reading. They are organized by when you might use them: before you read, while you read, and after you read.

Before You Read

You might think of "active reading" as something you do while, well, reading—but active reading can actually begin before you even crack open the book. The following strategies are all things you can do prior to the reading to prepare to make the most of the reading when it happens.

Plan for Time and Energy

I learned early on as a college student that the first thing I should always do before beginning a reading for school is I look to see how long it is so that I can estimate the time it will require to complete.

If you generally know how fast you read, you can do a simple calculation to estimate things. For example, if you can read a page a minute, then a 12-page reading will take you 12 minutes.

But this can be complicated by the fact that not all pages have the same number of words on them and that not all readings are of the same difficulty. You may read a basic fiction novel at one page a minute, but what about a huge science textbook page crammed with technical words, complex diagrams, and foreign concepts?

It may help, therefore, to not only estimate the time a reading will take but also the energy it will require—that is, the mental focus and attention you'll need to understand it. Knowing the time will help you plan your hours, days, and weeks so that you can fit in all the assigned reading, and knowing the energy will help you plan to do the most difficult readings when you are at your best.

Preview the Text

Previewing the text can help with figuring out the time and energy that will be required, but it can also help you see the overall flow and logic of a text and predict any obstacles that might slow you down.

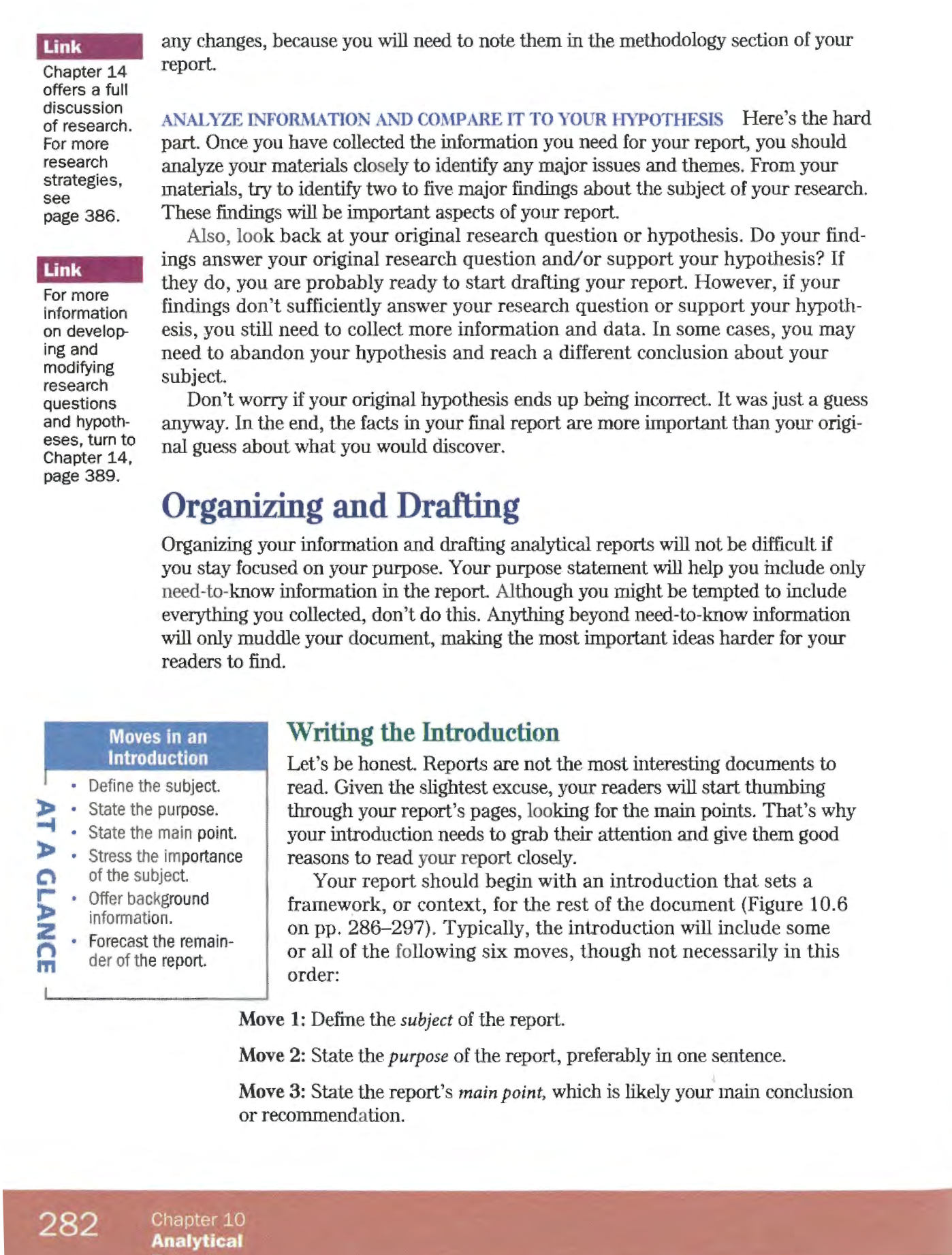

A simple way to preview a text is to quickly flip through (or scroll through) the pages to get a visual sense of how it is laid out. Most modern textbooks use two of even three levels of headings to visually and logically break up a text into sections and subsections. By taking note of how headings organize the text into chunks, you prepare yourself to more easily understand how it presents its various ideas and how they connect to each other.

This textbook page shows a level-1 heading in dark blue, a level-2 heading in green, a level-3 heading in light blue, and several sidebars. Paying attention to how a text is visually laid out can make moving through it quick and easy.

Previewing any diagrams or images can also give you a leg up on understanding what concepts might be covered and a head start on understanding them before you even begin reading.

You might also take note of any bolded words in the text (which are probably key vocabulary words) and can look up any that are unfamiliar to you.

Spot Read

If previewing a text by flipping through it to note obvious visual cues isn't enough, you might also engage in some spot reading. Spot reading is when you read short parts of the text to preview some of its key parts.

The most obvious bits that you might spot read are the introduction and conclusion. These are the places where most authors lay out their thesis and review the main points they made, so knowing those things in advance can make reading the whole thing later much easier.

As you preview a text, keep your eyes out for other passages that might be good to spot read. For example, many textbook chapters begin or end with detailed summaries that specifically preview or review a chapter's main points. Or you might notice that a heading indicates that a particular section of the text will be valuable to you for another reason.

Identify Your Purpose

It's hard to martial the time and energy to read something if you don't really know why you are reading it, so it's a good idea to identify a purpose for reading before you begin.

Your purpose could be an indirect motivator such as "I'm reading this because I want to get all As this semester" or "I'm reading this so I can impress that cute person in class" or "I'm reading this so as not to let down my mom." Indirect motivators, however, are fickle and can easily disappear or be overshadowed by more pressing or tangible issues.

Whenever possible, make such a purpose as short-term and immediate as possible (as in "My goal this week is to complete all my assigned reading by Wednesday") because tenuous connections to longer-term outcomes (such as the grade you'll earn months from now or the career you'll have years from now) aren't as motivating as you think they'll be.

Better still is to identify an direct motivator as your purpose. By that I mean an outcome that is directly tied to the reading. "I'm reading this so I can understand radioactive decay and half-life" or "I'm reading this to prepare for Tuesday's quiz" or "I'm reading this because I'm genuinely curious about the Civil War" are all great direct motivators because they not only give you a reason to get the reading finished but also a reason to actually understand and remember what you read.

Identify the Teacher's Purpose

Sometimes it's not your purpose but your teacher's purpose that is important. When I was in graduate school, I took a research methods class where the instructor assigned a huge number of scholarly research articles to be read before each class meeting. Each article was dense, complex, and long—and understanding them completely was a major challenge.

For several weeks, the other students and I were overwhelmed with the amount and difficulty of the reading we were assigned, and we were even more upset when we barely scratched the surface of any of the readings in our class discussions.Why, we wondered, would she assign so much reading and then only talk about a fraction of it?

Eventually, however, we figured out what our teacher hadn't said explicitly: her purpose in assigning these articles was not for us to read and understand every word. The topic of the class was research methods, and she only expected us to be prepared to discuss the methods used in the articles she assigned—she didn't care about the results and conclusions of any of the scholarly research studies, only the research methods used and how the writers explained them.

Knowing this cut down the amount and complexity of the reading we were expected to do by two-thirds at least, and we all could relax and focus—but only once we understood the teacher's purpose.

Identify Questions

Going one step further than knowing your purpose for reading is knowing exactly what information you need to have in hand when you are done.

Take a dictionary, for instance. Almost no one reads the dictionary by starting on page one and reading the entire thing sequentially. Rather, dictionary users always start with a question, such as "What does discombobulate mean?" Having this question leads them to find the exact page where the answer can be found, and they don't even read the whole page—they scan down to find the entry for discombobulate and just read that.°

You can apply this approach to many types of reading. Having a short list of questions gives you a way to sort between useful and less useful information, making reading (and remembering) much less labor-intensive.

For example, in the research methods class described above, I knew that the teacher's purpose was to help students examine research studies' methods. From there, I could further focus my reading by predicting the sorts of questions she was likely to ask in class:

- What research method did this study employ?

- Did the authors give enough detail about the specifics of their methods such that another researcher could replicate the study?

- Do the authors acknowledge any limitations to their methods, and if so, how do they justify these?

- Do you see any limitations or oversights in the methodology that the authors don't acknowledge?

Predicting and pre-answering these questions not only helped me complete the reading in a shorter time, but it made me look very smart during class discussions!

Define Key Terms

Oftentimes, your ability to comprehend a reading will revolve around your understanding of one or more key terms—in such a case, it makes sense to make sure you understand those terms before you jump into reading the full text.

I can't tell you how many times I made this mistake, trying to understand, say, a history reading that repeatedly used the term antebellum or a philosophy text that relied on the meaning of a priori°

When you preview a text or think about your purpose for reading, keep an eye out for key terms that you might want to know the definition of in advance—and then look them up!.

Spoil the Plot

When you read a murder mystery novel, you don't want to know who committed the murder until the very end of the book. That's reasonable.

But when you read most nonfiction material, especially textbooks for classes, there's absolutely no reason not to spoil the ending.

When I was a student, I found this especially useful whenever I was assigned to read philosophy. Philosophers aren't the most accessible writers—they often use difficult language and roundabout reasoning to work their way slowly from first principles to final points. They are often coming to us from a very different time, place, or culture. In other words, they are hard to understand.

So whenever I was assigned something scary from Aristotle, or Kant, or Foucault, I would first "spoil the ending" by going straight to Wikipedia or a similar resource and reading the abridged, simplified version of the theories I would soon read about in the original text.

If I didn't, I might find myself lost in a sea of ideas, unable to find any solid ground to stand on. But if I did, it made even difficult texts much easier to understand because I already knew where they were heading and the major turns on the route to that destination.

This technique doesn't only work for philosophy—I've used it for difficult scientific concepts, math, history, and more.

Why Bother with Pre-Reading Strategies?

Students often point out to me that engaging in any pre-reading strategy will only increase the time it takes to complete a reading.

And while that may generally be true, such a view is short-sighted. Yes, if your purpose is only to, as quickly as possible, run your eyes over all the assigned words, then doing any extra work will increase the time it takes to complete the task.

But if your purpose is to effectively and efficiently import the information so that you understand it and can use it for class and beyond, then these strategies can actually reduce the time and energy it takes to achieve that task. I found this out time and time again as a student myself when a text I had "read" but not really understood turned out to be more crucial to my success than I predicted, resulting in my having to reread and review the text again in order to be able to pass a test or write an essay.

As I matured as a student, I relied more and more on careful pre-reading strategies to more effectively allocate my time and effort so I was able to accomplish more with less.

While You Read

Okay, now we're at the heart of it: active reading strategies you can employ while you're actually reading. Here are several key strategies along with advice on how to implement them.

Photo by Nguyễn Hiệp on Unsplash

Annotate the Text

No doubt about it: Writing directly on what you are reading is a classic strategy to help you understand and remember things. Underlining, highlighting, making small notes in the margins, and other annotations keep you actively engaged with the text as you import its information, and they leave a trail for you to follow if you ever need to reread.

But a big mistake people tend to make with annotating is that they overdo it. Your annotating system doesn't have to be elaborate, involving 3 colorful pens, 5 highlighter colors, and 10 different symbols, all meant to help you dissect every possible meaning and question—but that's exactly what many new to this strategy do.

The problem is that an elaborate or over-complicated system creates a lot of friction. If you can't find all your highlighters, that becomes an excuse to not read. If you can't remember whether a small star in the margin means "I agree with this point" or "Look this up later," you get frustrated with yourself and are tempted to throw it all out the window.

A second problem is that if you over annotate a text, the whole system becomes useless. Highlighting is meant to draw the eye to key passages—so if 60% of the text is highlighted, what good is that?

My advice here, then, is to keep your annotating simple: one writing implement, few pre-determined symbols. Just be casual about it. And if annotating stressing you out, there are plenty of other strategies that you can opt for instead.

One other point: If you work with digital texts (ebooks, pdfs, etc.), you can still annotate, but how you do that will be governed by the app and device (laptop, tablet, phone) you are using. Not all PDF viewers, for example, offer the same annotation tools and the same interface, so it can be worth it to shop around a bit and find the app that you find most pleasant to use.

Take Notes

Not everyone likes to take notes directly on the text—some prefer to take notes on a separate page, and that's totally fine. Taking notes has most of the same benefits as annotating in that they both keep you actively engaged as you read.

Taking notes on a separate page, however, gives you a bit more space to expand and to draw, and the notes can travel independently of the text, which can be convenient. One disadvantage, however, is that you may feel compelled to copy out lines of text word for word, which you could just underline if you were annotating (though maybe copying passages out will help you recall them better?).

If you take notes digitally (e.g., in a Google Doc), you can potentially search your notes for specific words later on if needed, and you aren't reliant on carrying a separate notebook or keeping track of a sheet of paper.

Look Things Up

When reading, we often encounter words and concepts we aren't familiar with, and we have to decide what to do about them. For example, above I used the word "annotate," which may not be familiar to you. You could (1) plow on ahead without knowing its meaning, (2) try to infer its meaning from the context clues, or (3) pause your reading to look it up.

While some might encourage you to stop and look up any word you don't know, I would recommend a more strategic approach. Of course looking up unfamiliar words is generally good, but it can also slow down your reading significantly, sometimes to the point that you abandon it altogether.°

I recommend doing a bit of triage. If an unfamiliar word is obviously a key term in what you're reading (i.e., it appears in the title or thesis or is used repeatedly), then look it up. If a word isn't so crucial to the meaning of the whole, or if you can infer its meaning enough from context, maybe skip it to preserve your reading momentum.

Another strategy is to mark words you don't know as you see them (or jot them down on a scratch paper) but don't decide whether to look them up until later. That way you can mediate between the stress of potentially missing a key word and the stress of slowing down your reading.

Read Aloud or Listen to a Text

There's this persistent myth that "reading" only refers to using your eyes to visually import words into your head—that hearing a text isn't the same as reading a text.

Ridiculous!

Not everyone is naturally good at reading visually, and some people find it harder to focus on written texts for any length of time. So if it makes sense to you to listen to a text—either by finding an audiobook version or having a digital voice (or friend?) read aloud to you—you should absolutely do that. Similarly, if you find it easier to understand or focus by reading aloud to yourself (I often do), then feel free to do that.

One example for me is Shakespeare. Sure, I can read a Shakespeare play right off the page, but the language is archaic and difficult, and I find it wearying. But if I listen (or watch!) the same text performed, it's much easier to engage with and understand, and I find that the old-fashioned, unfamiliar words are much easier to understand in context.

Keep in mind, however, that listening comes with its own set of potential strengths and weaknesses. You free your eyes and hands up to do other things (take notes, do dishes, go jogging), but you need to be honest with yourself. If listening to a text while, say, exercising helps you focus and understand better, then great. But if it distracts you from effectively importing the information, you might be better served by using a different strategy.

Look for Signposts

Nonfiction texts almost always contain signposts to guide the reader along the logical flow of ideas leading from first principles to final thoughts. If you are only reading casually, you might not notice these signposts at all, and as a result you might find yourself lost, especially in a longer or more complex piece of writing.

If you actively look for these signposts, however, you might find even difficult texts much easier to understand.

Internal signposts are words, phrases, and sentences within the text itself that indicate to the reader the underlying structure of a text. Here are some common internal signposts you might notice:

- Thesis statements define an author's main point or argument, and they are most often found in an introduction and then restated in the conclusion.

- Forecasting statements, which often follow or are combined with theses, are sentences that lay out the various subtopics that will be covered along the way.

- Topic sentences define the topic or purpose of smaller section of a text. If a text is divided into sections, you might find a topic sentence or two at the beginning of the section laying out what the section will cover and how it relates to the larger flow of the text. Similarly, individual paragraphs may begin with topic sentences defining what the paragraph will cover.

- Transitions indicate shifts in direction in the logical flow of a text. They can take the form of words and phrases like "on the other hand" or "conversely," or they can comprise entire sentences. In fact, topic sentences are often paired with or act as transitions.

External signposts are typographic and formatting elements that give a visual indication to the reader of the structure of a text. Here are some common external signposts you might notice:

- Headings create visual breaks and divide a text into major sections. The text of the heading is usually a strong clue about the topic or purpose of the section it heads.

- Subheadings can be used to subdivide sections into subsections, which is often useful for particularly long or complex texts (like this one!). There might even be sub-subheadings or sub-sub-subheadings!

- Lists can be bulleted or numbered, and they visually indicate that the information being presented consists of multiple elements that are similar in importance (bullets) or should be considered sequentially (numbers).

- Bold and Italics are often used to draw the reader's attention to key words and phrases within paragraphs and thus provide a clue to the writer's mind.

Skim, Scan, Skip

While the other active reading strategies mentioned are all about focusing more intensively on a text, not all texts require your full attention. Sometimes, the right move is to not read every word in a text closely but instead to carefully and strategically skim or scan a text. In other cases, you might skip a reading entirely.

How will you know when to skim, scan, or skip? You usually need to employ of the pre-reading strategies in order to determine this. Previewing a text, identifying yours or your teacher's purpose, or spot reading can give you needed information to make a careful choice.

To be clear, none of these should be your default mode of reading if you plan to succeed in school. Choosing to skim, scan, or skip a reading should never be an unconscious choice or the unavoidable effect of procrastination. And you should always remain aware that you could be depriving your peers of the benefit of whatever contributions you might have made to the class community had you done a more thorough job.

But if we're being honest, there will be weeks when there is literally not enough time and energy to complete every reading, even for the most dedicated and conscientious student. In such cases, a strategic move might be to make careful decisions about where to spend your limited resources and where to skim, scan, or skip certain readings.

After You Read

It would be great if completing a reading were the end of it, but quite often students find that they need to employ post-reading strategies in order to complete or guarantee their learning.

Strategies such as the following are especially useful when preparing for a test or writing an essay that relies on key readings.

Review Your Annotations or Notes

If you took the time to annotate a text or take notes, you might find that present-you is thanking past-you for their efforts. There may not be a faster or more efficient way to prepare for a test or otherwise revisit a text than to review your own notes. They can provide a window into your own thinking in a previous time and can save you the trouble of needed to reread or even skim the text again.

And don't underestimate adding to your notes as well. If you have your notes with you in class, say, as the reading is being discussed, take that opportunity to annotate your annotations, adding emphasis or new entries to reflect how your thinking shifts in relation to the class discussion or things your instructor says.

One thing to beware of, however, is that if you only rely on your notes, you can potentially blind yourself to seeing new depths in a text. Occasionally it can be valuable to reread a text without your notes to free yourself up to have potential new insights.

Explain It To Someone

There's probably no better test of your understanding of a text than whether you can explain it to someone else. Their face will tell you whether you are successful or not.

Photo by Metin Ozer on Unsplash

This doesn't just apply to the plot of a complicated novel like Oliver Twist or Pride and Prejudice either. Try explaining how light operates as both a wave and a particle; or how the Federalist papers contributed to the ratification of the U.S. Constitution; or how Aristotle's three rhetorical appeals of ethos, logos, and pathos work—you'll quickly find out what parts of the reading stuck with you and which parts you might need to revisit.

Summarize

Similar to explaining your reading to someone else, writing a summary of a reading is a way of forcing yourself to identify the big-picture structure of what you read. You have to sort through all you read and determine what the main idea is, what supports that main idea, and what is merely small details not worth mentioning in a short summary.

It doesn't have to be written either. You could just say it aloud, or record a voice note, or use any medium that is useful to you.

Diagram

Synthesizing what you've read into a visual form such as a diagram can be a powerful way to ensure that you not only remember what you read but that you've processed the information into a meaningful whole of your own.

A diagram can take any form you want (though boxes/bubbles connected by lines is a common approach). If you've paid close attention to a text's structure, as revealed by its signposting, your diagram could be a visual representation of that structure. Or you might find that it's more useful to pull out the ideas found in a reading and impose your own original logical structure to them, connecting them in ways the author didn't explicitly reveal. You might associate ideas with particular colors, shapes, or images to help you remember them, or you could invent other mnemonic devices to help recall information later.

Connect to Other Readings

It's tempting to treat each reading assignment as independent of all others, as something that needs to be understood on its own—but in reality everything we read is related to everything else in some way. In fact, your instructors are probably hoping you will identify the connections between assorted readings they assign because that kind of synthesizing is a key aspect of a well-rounded college education and evidence that students are learning effectively.

So it might be worth your time and energy to deliberately look for and note such connections. You could use any of the above post-reading strategies to explore and record those connections. Don't be surprised if your teacher's face lights up if you share such a connection during a class discussion.

And don't stop yourself at the border of a single class. Finding connections between various readings in, say, your history class is one thing, but finding connections among the readings in all your classes—English, history, science, economics, psychology, and more—is also a valid and useful strategy. It will not only help you remember and process individual readings, but it will also train your mind to work in exactly the way a university hopes it will. The word university, after all, derives from the Latin universitas, which means "the whole" and conjures an image of all knowledge being combined into a coherent whole.

Conclusion

You might find this list of active reading strategies a bit overwhelming, but just remember that you aren't expected to do all of them all the time. A key part of using strategies is being strategic—in other words, you should carefully consider which strategies to employ at which times.

Think about the length, difficulty, and importance of what you need to read, and choose one or more strategies to match. It'll take practice to consistently choose the right strategies each time, but you'll find that not only are you able to choose better, the strategies you use will become easier and more efficient as you practice them as well.