The very name of this article implies that the concept of "writing for the web" holds together as a uniform thing that can be defined, can have its limits surveyed and marked out, and can be distinguished from other forms of writing. Nailing down the concept is much more complicated due to the simple fact that the two key terms in the phrase—"writing" and "the web"—each contain multitudes.

I'm sure I don't need to convince you that there are many many kinds of writing out there, nor are you unaware of the astonishing diversity of what the internet has to offer. Multiply the two together, and you can see what a hopeless exercise defining the concept is going to be. As Nicholas Carr pointed out in The Atlantic well over a decade ago:

When the Net absorbs a medium, that medium is re-created in the Net’s image. It injects the medium’s content with hyperlinks, blinking ads, and other digital gewgaws, and it surrounds the content with the content of all the other media it has absorbed. A new e-mail message, for instance, may announce its arrival as we’re glancing over the latest headlines at a newspaper’s site. The result is to scatter our attention and diffuse our concentration.

—Nicholas Carr, Is Google Making Us Stupid?"

These words were published in 2008, barely a year after the original iPhone hit the market. Even if you've been asleep since then, you can't help but have noticed how dramatically the internet has both pervaded our lives and mutated into ever new forms during the smartphone era. Writing for the web has only grown in importance and in variety during that time.

Despite these difficulties, we must push forward in our impossible task. Rather than come at things head-on, however, I will attempt to overview the concept of writing for the web by discussing these four questions (click any of them to skip down to that section):

- How is Writing For the Web Different Than Writing for Print?

- How Has Writing for the Web Evolved Over Time?

- What Kind of Writing Exists on the Web Today?

- What Skills Does One Need to Write For the Web?

Ready? Let's get to it.

How is Writing For the Web Different Than Writing for Print?

This is a good question, and the answer may not be as obvious as it would seem given that many of us have spent most of our lives surrounded by digital text. Because hypertext is so ubiquitous, it hasn’t occurred to many of us to consider exactly what distinguishes it from the printed text you see on signs or in books.

Here are four ways that hypertext and writing in online environments are different from print.

Hypertext Is, Well, Hyper

Print text—ink on paper—is a static medium. It doesn’t change before your eyes, and you can’t interact with it except for in your mind.° Changing what has been printed (to fix a typo, for example) requires printing it all over again.

Hypertext, on the other hand, is dynamic. A web designer can change a single letter on a single page, and someone viewing the page thousands of miles away can hit “refresh” on their browser and have the change instantly before them. Text can change form when a mouse pointer hovers over it. You can click a link, and it will propel you toward another page at lightning speed. Wikis allow entire groups of users to all contribute to and edit the same text, and software like Google Docs allows the same collaborations to happen in real time.

Effectively writing for the web requires one to understand this, the dynamic nature of hypertext.

The Immediacy of the Audience

Second, the audience as always so much closer when you write for an online environment. Think about it: the traditional printing process adds layer after layer and a lot of time between the writer and the reader:

- Some author somewhere toils away in their basement for months or years, crafting a fully realized book.

- They send it to an agent, who shops it around at publishers.

- When a publisher accepts the manuscript, it then is edited (and fact-checked, if it is nonfiction), which involves more back-and-forth with the author to settle on a version of the text that both the author and the publisher are happy with.

- Then it gets typeset, proofread, sent out for reviews and blurbs, printed as galley proofs, proofread again, and then finally printed and bound as books before being sent to bookstores.

Only after all that time and activity can a reader then go to the bookstore and pick up an actual copy of the book. They take it home, open it up, notice a typo on page 6, and write the author—but it’s too late. Thousands of copies or more have been manufactured, so any revisions or corrections will have to wait for a second edition, and they'll have to be filtered through all the layers of editors, agents, and managers.

Writing for an online environment collapses all of that time and distance down to almost nothing. You pick up your smartphone, open Twitter, write 140 characters, hit send—

—and millions of users worldwide can see it, like it, retweet it, reply to it.

The internet gives nearly everyone the power that used to be guarded by the gatekeepers of the publishing industry. Almost anyone now can have a voice that might reach to the very tips of humanity with almost no effort.

It’s amazing, and it’s a little scary.

The Audience Has Power Too

Another thing that distinguishes print from hypertext: the audience has much more power than they used to.

It used to be that writers and publishers had absolute power to choose much of how audiences would interact with a text. Scroll or codex. Hardback or paperback. Large print or tiny font. Times New Roman or Comic Sans. Large margins good for taking notes in, or lines that fill the page and are hard not to lose one’s place in. English or some other language.

When we send our text out in digital formats, a lot of that power is now in the hands of the audience. They choose the device used to access the text—laptop, tablet, or phone, for example—and they can resize and restyle the text to best fit their needs.° They can choose to have Alexa read the words aloud to them while they bake cookies, and they can play that podcast at quadruple speed while they shower.

A lot of this transfer of power is good, as it can increase access for those with differences in vision, hearing, mobility, and other abilities. But some of it is not so good. Remember that tweet you sent? You may later realize that it was insensitive or ill-conceived, or maybe you get ratioed. You still have some power as the author of the tweet—you could delete it. But that doesn’t mean it’ll disappear from everyone’s device and from the internet entirely. Chances are that it has been cached, or someone out there has probably already grabbed a screenshot of it, and it’ll be floating around in cyberspace forever. That’s part of the audience’s power too.

The Hidden Cost of Content

A final way webtexts are different from print ones is that the cost of producing web content seems to be zero or close to it. I say "seems" because it's not true.

When you hold a book, it's relatively easy to register its value, or the cost it took to produce. The paper and ink are tangible reminders of the physical acts of printing, binding, and distributing that the publisher had to undergo to put the book in your hands. Flipping the pages and seeing word after word arranged into sentences, paragraphs, and chapters makes it easy to link the book's physical value to the intangible value of the writer's labor of composing. There's a very real instinct that to take the book without paying for it would be an act of theft, both physical and intellectual.

On the internet, however, the nature of the medium and its history obscure that implicit sense of a text's value. You can't hold the words, and they occupy almost no physical space, weigh next to nothing, composed as they are of electrons. More than that, digital media are limitlessly reproducible—where a book must be physically printed, almost anything on the internet can be copied and pasted with the merest of hand motions. Since the very beginning, the majority of the internet's content has been available for free, and rules against copying and reposting content have been unclear, or ignored, or unenforceable. Digital media's reproducibility and the Internet's history of taking have resulted in a widespread culture—however unintentional—of devaluing content and its creation.°

Worse still, even when you contemplate the cost of a webtext's creation, it doesn't seem to add much value. Whereas adding color or images to a physical book would obviously and directly increase the cost of its printing, it costs nothing to add color and images—as well as audio and video and who knows what else—to a webpage. And the cost of hosting a website is pennies a day, or nothing at all if you just use social media or one of the hundreds of free website creation services.

Except it doesn't cost nothing. Sure, a text-only webpage and one that includes photographs both cost essentially the same amount to transmit over the internet to your computer or device—it's all just bits and bytes, after all. But the content of the webpage took labor to produce. Just as the book's value is not only in the cost of physical production but in the intellectual labor of its writer and the artistic labor of its photographer, so is a webtext's value. The webtext's physical production cost may be near zero, but the intellectual and artistic labor are exactly the same as they would be in print form.

All told, it's clear that writing for the web is quite a different animal than writing for print. Hypertext moves fast, brings the audience close, transfers power to the reader, and hides the true cost of production. Appreciating these differences is crucial to being able to write well on the web.

How Has Writing for the Web Evolved Over Time?

Hypertext wasn’t always so powerful. Since the internet became widely available in the early 90s, it has gone through several major shifts that have changed how we write for it. Here’s a very brief history of those changes.

Web 1.0

The early days of the web were dominated by static webpages. Someone would open their browser and navigate to a page, and the server would send the HTML file containing the page. All users would see the same content, and they couldn’t interact with it in any significant way other than to read it and click the links.

The web at this time was built on HTML, or Hypertext Markup Language. To get your writing on the web, you either had to learn how to use HTML or hire someone who did. This mean that the acts of writing and designing for the web were often one and the same.

HTML is a markup language, not a programming language. In other words, it allows you to mark a text so that a web browser knows what it is and how to display it. This is done by surrounding text with tags. For example, if you wanted to tell the browser to render a bit of text in bold, you would nest it within tags like this—

<b>This text should be in bold.</b>

—and the browser would render that text like this:

This text should be in bold.

In early HTML you could add additional formatting information, like the size, color, and alignment (left, right, or center) of the text.

More than just formatting, HTML is used to create the structure of a document. Tags like <head>, <body>, <p> (meaning paragraph), and <h1> (meaning a level-1 heading) tell the browser what parts of the document are what.

In other words, early HTML was used to determine both the structure and the formatting of webpages. For simple websites with only a few pages, this system worked well. But as sites got larger and more complex, a problem arose—say you decided to change the color of links from blue to green, or you wanted all your level-1 headers to be centered instead of aligned to the left margin. You would have to search through every page on your site and manually change each tag to the new formatting. If you were running a site like Amazon, even in the 90s, this would be basically impossible.

The solution came in the form of CSS, or Cascading Style Sheets, which allow designers to separate the formatting of a webpage from its structure. In simple terms, elements in the HTML document can be assigned a selector, most often in the form of a class. The selector is part of the opening tag, like this:

<p class=“dogs”>Here’s a paragraph about dogs.</p>

A separate CSS file, which is linked to the HTML file, finds all the elements marked with the class “dogs” and applies the same formatting to it, as specified in the CSS file, like this:

.dogs { color: white;

font-size: 24px; }

Since a single CSS file can be attached to any number of HTML files, the web designer only has to style the text one time, in one place, and then any text in any attached HTML file that is assigned to that class will be formatted that way. And if the designer needs to make a change, he or she can input that change just once on the stylesheet and that change will then cascade down to every attached HTML file.°

Introducing CSS made it so that the content and structure of a webpage resided in the HTML file while the formatting resided in the CSS file. In the same way, the acts of writing content for the web and formatting that content could be more easily separated now.

At the same time, more powerful web design software made creating websites easier than ever, putting content creation in the hands of less technically minded people.

Web 2.0

There were other changes happening to the web that made things more dynamic. JavaScript, PHP, and other technology began to allow actual programming to happen in and around webpages, so they no longer had to be just static text but could accept inputs from the viewer and could change what they displayed based on factors surrounding the user and his or her location.

This allowed for things like personalized, private pages to be served up on the fly, such as a university student logging into their school website and seeing private content meant only for them—tuition statements, grades, a class schedule, etc. It also allowed for simple video games to be created and played within an internet browser.

But most important of all, it allowed viewers of webpages to contribute to those pages, directly adding to or changing the content. This ushered in the rise of social media and what we now call Web 2.0.

Before Web 2.0, anyone could make a webpage if they had the server space and the technical knowhow. But new sites like MySpace made it so that anyone could create and update a personalized webpage merely by typing into textboxes on a website and hitting “submit.” The software would take the text, apply the needed HTML/CSS markup, and embed it in a ready-made webpage that was hosted by the parent site.

Around this time, blogs were also becoming popular. Short for weblogs, blogs are websites consisting of posts usually served up in reverse chronological order, like a journal but backwards, beginning with the more recent content and moving back through time. Users of sites like Blogspot and Blogger could just choose a template from a list and then create posts with a simple interface—the software handled not only the markup and coding of each individual post but also maintained the overall website structure, automatically linking the pages together with archives, keywords, and categories. More than that, blogs and social media software allowed people who visited the pages to leave comments, turning nearly every page of the internet into a discussion board waiting to happen.

This explosion of user-generated content and social interaction is what defines the Web 2.0 era, and it continues today with Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and hundreds of other web-based communication services. Writing for the web is now as easy as typing—easier, since we don’t need to spell to use emoji and don’t need to even move our fingers to dictate a text to our phones.°

Web 3.0?

Nowadays, many users interact with, write for, comment on, and react to web-based writing without ever using a browser like Firefox or Chrome—doing it instead through apps like Facebook and Twitter than live directly on their phones' home screens. Some of them probably don’t even think about this as writing for the web, since the once-familiar process of using a modem to establish a phone line-based web connection and then launching a web browser on a desktop computer monitor are long gone.

But tapping the Facebook app on a smartphone screen is a form of connecting to the internet. So is saying “Alexa” or “Hey, Siri.” So is wearing a Fitbit or smartwatch. So is streaming a show from Hulu on your web-enabled TV, or hooking up a Nest camera so you can check on your dog while you’re at work.

Almost everything you touch on a smartphone connects you to the internet.

Photo by Sara Kurfeß on Unsplash

Where the internet used to be a thing that came to us via tubes and was contained in a window on a monitor, now it is all around us all the time. We are literally swimming through the wifi networks that fill our houses and the 4G (now 5G) cell networks that fill our towns, all while dozens of devices, sensors, wearables, and appliances connect to it and exchange data with it constantly.

This evolution is often called the Internet of Things (IoT) because of the proliferation of internet-connected objects and devices, many of which lack screens. Combined with the growing use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to automate the collection, processing, and use of the tons and tons of data that is being collected, some thinkers refer to the present (or still approaching) era as Web 3.0.

We can't really predict what writing for the web will look like in Web 3.0 and beyond—it's changing too quickly to keep track of. For example, a new job exists that didn't just a few years ago: writing jokes for Alexa or Siri.

What Kind of Writing Exists on the Web Today?

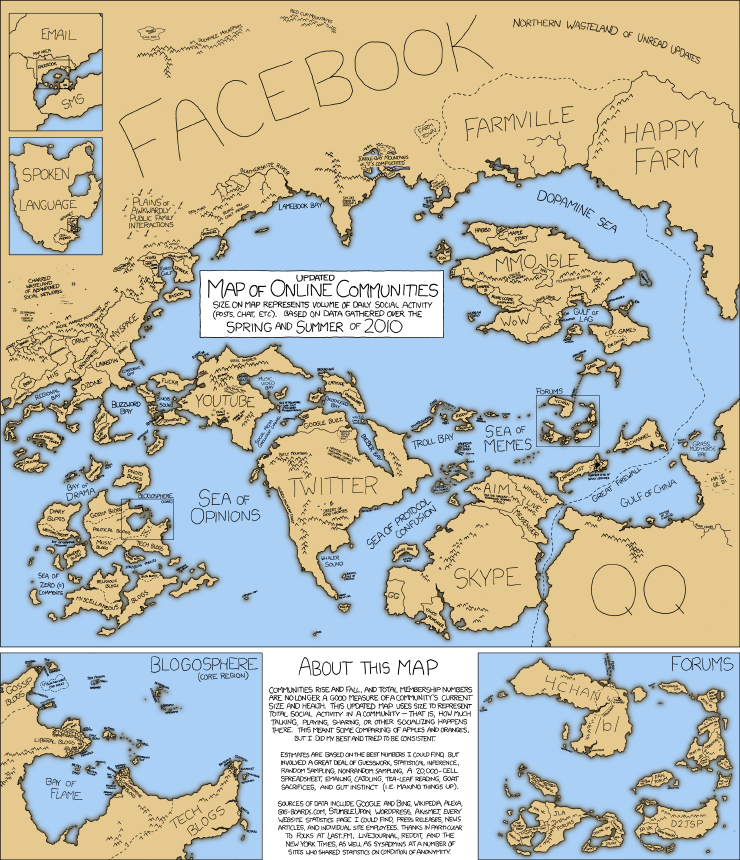

The short answer is "all kinds." But that’s not very useful for us who are trying to develop our abilities to write better for the web, so let’s see if we can create a more detailed map of what’s out there.

First off, we need to set some limits or we’ll go crazy with the possibilities. Let’s confine ourselves primarily to text, leaving visual and audio media out of our definition of “writing.” Also, let’s focus on traditional websites, the kind of places you mostly visit by using Chrome, Safari, or Firefox.

So what kind of sites exist and what kind of writing happens on each one? Let’s see if we can make a list that covers most of the bases.

Professional Media Outlets

One big category of website that produces writing are the professional media outlets that employ journalists, editors, researchers, and writers to produce daily or weekly content. On these sites, the writing itself is the product.

Many of these sites began as traditional media outlets like newspapers, magazines, and television stations (think of the New York Times, Sports Illustrated, or Food Network). Others began life on the internet (Slate is a web-magazine that never ran a monthly issue, and HuffPost [originally The Huffington Post] began as a sort of online newspaper that never existed on actual newsprint).

The Atlantic, published since 1857, has somehow weathered every shift to the media landscape for over a century and a half.

It’s important to understand a bit of the history of how sites like these make money. Back in the print-only days, newspapers and magazines made money in two main ways: they charged readers to read (either buying the item on a newsstand or purchasing a subscription) and they ran ads in their pages. When media outlets first went online, they mostly just posted print articles online and let anyone read them for free.

Then the bottom fell out of, well, everything. With the rise of devices and social media, more and more readers began to consume more and more content online, and the print subscription revenue for many newspapers and magazines all but dried up, which had the added effect of driving down revenue from selling ads—advertisers don’t pay as much for space when no one is reading. At the same time, Google and Facebook cornered the market on online advertising, which prevented media outlets from fully supplementing their income with online ads. And because online content had always been free, outlets who put their content behind a paywall found that no one was willing to purchase a subscription. The result was the biggest shakeup of the journalism industry in history: hundreds of newspapers and magazines folded, hundreds of new media sites were born (and most of them died), and the entire landscape changed.

Fast-forward to today (I'm writing in 2020) and things are changing again. Thanks in part to the success of subscription-based media companies like Netflix and Hulu, and due to some outlets’ success in creating highly desirable online content, some media outlets like the New York Times, Slate, and the Atlantic are seeing rising numbers of paid subscriptions, and revenue from online ads is higher than ever. The industry is still very fragile, but new business models are carving out a path.

One of the big shifts that happened as these outlets moved online is that the traditional production cycle was upended. Newspapers used to publish once or twice a day, magazines once a week or once a month. Now, content of all types is published throughout the day, every day. The Times, for example, produces its typical articles, but it also produces blogs, podcasts, documentaries, virtual reality videos, online puzzles, a Cooking app, and dozens of other types of content to stay afloat.

These shifts mean that the business of writing or freelancing for such outlets is more precarious than ever, but opportunities to produce interesting online content are more prevalent than ever because readers are voracious in their desire for more and more content.°

Retail Sites and Restaurants

Another major category of website includes those trying to sell you something. Amazon is just about the largest of these, but tens of thousands of sites advertise products that can be ordered online and sent to your home. Some, like Amazon and Etsy, aggregate sellers into a single marketplace. Others, like J. Crew or Ikea, sell only the company’s products, as they would in stores.

Someone has to write all those product descriptions.

On these sites, the writing isn’t the product, but it helps to sell it. Companies hire writers to write product descriptions, buying guides, return policies, and other types of marketing copy. And they encourage those who have purchased products to write product reviews in the hope that they will inspire other customers to make purchases.

About pages, like this one from KIM+ONO, can help create the idea of a brand, which can be very motivating to consumers.

Public Faces of Companies, Professionals, Artists, and Organizations

Not all companies sell things directly to consumers online. Many maintain a web presence to drum up business for their services or to help create or maintain a public image. For example, an engineering firm’s website has no cart and no payment page; instead, it may showcase some of the firm’s past work and establish a brand image that potential clients might respond favorably to. Hospitals, museums, universities, churches, charities, tattoo parlors and other organizations and businesses all maintain websites to provide the public with information about the products and services they offer. Actors, artists, accountants, real estate agents, people running for office, and other professionals also use websites as the public face of their brand or business.°

The homepage of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Much of the writing contained on sites like these could be considered marketing copy of one type or another—the sites serve as advertisements. Some of this is contained on static pages and may include mission statements, biographies of founders and employees, testimonials of satisfied customers, and examples of past successes. In addition to this, many websites have a blog-like newsroom, where press releases can be posted. Press releases are public announcements of new programs, initiatives, achievements, and other events that organizations use to generate interest and excitement.

The news page of the American Red Cross

Government

City, state, and federal government bodies and figures use their websites to share important information with the public about utilities, school, public services, parks and recreation programs, reports and proceedings, statistics, elections, emergencies, and more.

Social Media

You are no doubt familiar with social media sites—Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter being the biggest examples today—and they probably make up a sizable portion of your weekly interaction with the web.

Social media is in some ways the inverse of the professional media. Like professional media, social media sites almost always make their income by selling ads rather than forcing users to pay a subscription. But unlike professional media sites, which must pay writers to produce content for them, social media sites get all the content they want for free from the users. You write a Facebook post about how your day was or post a pic on Instagram of what you ate for dinner, and your friends log on to see it, incidentally seeing half a dozen ads and putting money in Facebook’s pocket.°

It’s a business model so insanely, brilliantly efficient and ruthless that it has completely rewritten how the advertising and journalism industries work (as discussed above). In fact, a large part of professional media outlets’ business strategy is to produce content that can go viral on social media so that more and more users will end up at their sites, where they might click ads or be inspired to purchase a subscription.°

Anyway, it’s basically impossible to characterize what writing looks like on social media, because it looks like everything. Every random thought anyone had is now content.

However, because so many professional media outlets and businesses now rely on social media to act as marketing and advertising platforms, social media-based brand management is a legitimate writing job now. Retail outlets post series of images on Instagram with tasty captions meant to attract buyers. Restaurants interact with local customers on their Facebook pages to create an image of being a neighborhood institution. Magazines post blurbs from their cover stories as Snapchat stories. Wendy’s roasts people on Twitter.

Wikis, Tutorials, and Other Resources

One of the great promises of the early web was that it would connect virtually everyone to virtually all the world’s information, and in one way, that promise was fulfilled. The internet is an incredible resource for learning about things and how to do things. Since the very beginning, people have freely shared their knowledge online, and the results are often lovely.°

Wikis are websites that use Web 2.0 technology to allow users to add to or alter the page content itself. Perhaps the most famous example of this is Wikipedia, which crowd-sources, crowd-edits, and crowd-polices its content with astonishing success.

There are lots of other wikis and wiki-style sites out there that seek to collect and organize encyclopedic information about every known topic and interest area. You’re probably familiar with imdb.com, which collects information about movies and television shows, and if you have a special interest in, well, anything—video games, knitting, gardening, dog breeding, birdwatching, model trains, vintage lawn ornaments, or literally almost anything else—chances are there’s more than one wiki or fan site out there attempting to chronicle the topic in its entirety.

Tutorials and instructions are another major category of this type of site. Wikihow.com, Instructables.com, allrecipes.com, OWL at Purdue, and iFixit.com are all examples of sites offering information on how to do things. The writing done on these sites is, generally, unpaid, and as a result it can be of varying quality.

Wikipedia is a nonprofit organization that runs on grants and donations and offers it content free without ads or subscriptions. Most other sites generate revenue through ads, and some operate on the “freemium” model (buying a paid subscription removes ads and unlocks bonus content, but otherwise the site is free).

Personal Websites, Blogs, and Fan Sites

The web has always been populated by personal sites, the hobbies of millions of people who just enjoy pushing HTML around for fun. My own first website, which I built in a high school class but never put online, was a Phish fan site. Later I used my growing skills to put a Choose Your Own Adventure novel that I wrote for my long-distance girlfriend online for her to read and click through.°

Personal sites, fan sites, and blogs can cross over with lots of the other types of sites listed above. Whereas blogs were originally just personal journal entries for anyone to read, along the way people figured out how to monetize them, leading to an explosion of cooking blogs, mommy blogs, DIY blogs, and blogs of every other conceivable topic. Blogs have been turned into bestsellers and films; they have been grown into viable media empires.

Leftovers and Crossovers

We haven't really covered nearly every type of website where writing is happening, but we've covered a lot of the big ones. Here are a few additional odds and ends to be aware of:

- Entertainment sites: Someone has to write all those show and episode descriptions on Hulu and Netflix, right?

- Crowdfunding sites: Places like Kickstarter and Gofundme have recently become major hubs for internet traffic, and there's stiff competition to get projects and causes funded. A major way users are convinced to donate their money is by the persuasive writing presented for each project or cause.

- Newsletters: A big trend right now (2020) is for writers and journalists to write daily or weekly newsletters that they email to a group of subscribers. There are platforms to facilitate and even monetize this, of course.

- Games and Apps: Everything we've discussed can be repackaged as or translated into a smartphone app, which means more content generated by more writers. Smartphone-based video games need writers who can craft dialogue, helps, and tutorials.

- All the garbage: So much of the content on the internet serves no purpose but to (1) fool search engines by flooding cyberspace with links to and from other sites so they will rank higher in the Google results page and (2) garner accidental ad clicks from the hapless saps who end up on such pages.

Additionally, there are crossovers of every conceivable kind, sites that encompass aspects of multiple categories. I mentioned some above, but here are a few more examples:

- Food Network's website is a professional media site, but it is also a marketing page and delivery device for the network's television shows as well as a repository of tutorials (in the form of recipes).

- eBay and Etsy bring the personal into the retail space by enabling users to sell their own wares and craft their own marketing copy.

- All the heavily monetized blogs and blogs started and run by businesses take what was originally a personal form and bring it into the marketing and retail space in various ways, for example, by using affiliate links°, ads, and cross-linking for search engine optimization purposes.

- Product review sites mix elements of retail and tutorial sites and come in every possible flavor, from the lowly personal site reviewing knitting gear to major media company-owned sites (like CNET or Wirecutter) that review all manner of consumer goods.

By the time you read this, the internet will have evolved again, ever creating new forms. It's exhausting to live in the future.

What Skills Does One Need to Write For the Web?

Fundamentally speaking, the only skill you need to write on the web is the ability to write. Good, clear prose and original, engaging ideas are always the most important currency regardless of sphere you write in.

However, from a practical standpoint, it can really help if you gather a few extra skills. Just as the internet itself is a huge mashup of everything, successful web writers tend to encompass a variety of skills. Here are some you might consider adding to your skillset:

- Journalism: If you want to write for any professional media outlet—as a freelancer or staff writer—it'll help to know something about journalistic writing and ethics. How to write in the inverted pyramid model, how to interview, how to manage your bias while reporting: all these things will make the writing easier, and demonstrating you have these skills might be crucial to convincing an editor to hire you.

- Web Design: You don't need to be a full-on coder, of course, but knowing the fundamentals of HTML and CSS will make you a much more effective web writer. Being able to look under the hood and diagnose a problem, to solve a simple layout issues yourself, to communicate with the real designers and coders if necessary, and to ensure your copy is accessible° are all very useful skills.

- Editing: Because writing on the web collapses much of the time and distance between the writer and reader compared to traditional publishing, it can help to develop your skills as an editor. Learning to proofread your own work for simple errors, to read aloud and find unclear or unwieldy passages, and to be able to find answers to questions about usage will all serve you well.

- Technical Communication: If you hope to do anything in the instructive/tutorial vein on the web, sharpening your technical communication skills will be valuable. Lots of writing on the web takes the form of translating technical or esoteric knowledge to readers with limited experience or attention spans (and research shows reading on a screen changes the way readers' eyes move across text), so the principles that guide technical communicators can guide you as well.

- Graphic Design: Being able to provide your own visual content to accompany your web writing can be a great asset, especially to media outlets whose budgets for professionally produced photography, infographics, etc. are constantly shrinking. It can also help you retain more control of your output when publishing on others' platforms.

- Public Relations and Marketing: So much writing on the web—both professional and personal—revolves around generating interest and engagement, often in the form of press releases, social media posts, and other genres of marketing. Therefore, learning a little something about the theory and practice of public relations can help you craft effective promotional copy.

Diversifying your talents won't just help you with the practical concerns of producing quality web writing—it can also help you secure employment. The business-speak term for being able to more than just what your job title implies is silo-busting, and positioning yourself as a silo-buster can play very well in the job market and freelance spheres.

Consider the perspective of a manager who is hiring for a writing position. Say the manager is looking at a handful of resumés and portfolios, and each of them present candidates who are accomplished writers who could do the job. But your resumé presents you as a silo-buster, able to do more than the job at hand but many of the adjacent tasks that might come up. That represents real value to the employer since he or she will get the skills of several employees for the price of one. The employer might even have a longer-term picture in mind beyond what is in the job ad and can thus see you as the right mix of skills for a future project or team.

Conclusion

In the end, perhaps the only firm conclusion to draw about the concept of "writing for the web" is that we can't draw any firm conclusions. Just as the internet itself is too big and various to define in any way beyond the sketchiest outline, writing for it is likewise too diffuse to nail down entirely. What you do and how you do it will depend entirely on the context you work in—as a hobbyist, a professional, or a freelancer, as a marketer, journalist, or technical writer.

There's one final point I'd like to make, and that is that writing for the web doesn't only happen on the web anymore. Just as the internet has migrated from our computers to our phones and from our phones to our fridges, televisions, sprinkler systems, and just about everything else, so has writing for the web influenced all the other kinds of writing out there to some degree. Nicholas Carr says it better than I can:

The Net’s influence doesn’t end at the edges of a computer screen, either. As people’s minds become attuned to the crazy quilt of Internet media, traditional media have to adapt to the audience’s new expectations. Television programs add text crawls and pop-up ads, and magazines and newspapers shorten their articles, introduce capsule summaries, and crowd their pages with easy-to-browse info-snippets.…Old media have little choice but to play by the new-media rules.

Never has a communications system played so many roles in our lives—or exerted such broad influence over our thoughts—as the Internet does today.

—Nicholas Carr, Is Google Making Us Stupid?"

As I pointed out above, he was right in 2008—but the subsequent years have proven him far more right than anyone expected.