From time to time, as a student or a professional, you’ll want (or be assigned) to embark on a larger-than-average project, something that could require a significant investment of time, energy, or other resources to bring to completion. For example:

- A student may complete a thesis or dissertation

- A team at an advertising firm may create an ad campaign

- A company employee may undertake a reorganization of the office travel approval process

While it would be great if you could just launch into such projects with a devil-may-care attitude and see where things lead you, in many situations you’ll need to ask for permission first. After all, other people are probably involved, either because they are financing the project or otherwise invested. A proposal—that is, a document describing the project and outlining the plan and required resources for its completion—is a typical way one asks for that permission.

Writing proposals can be a drag. They require you to work out details you’d probably prefer to work out later, being specific about things you don’t know the specifics of. A timeline? How about we just say “it’ll be done when it’s done”? A budget? C’mon, I don’t know how much it’ll cost, but I’m positive the final results will be totally worth it. A detailed outline of exactly what the project will and won’t include? I like to work by feel, you know? I’ll just know what should be included and what shouldn’t when I see it, right?

Why can’t people just trust us to figure things out as we go?

The Rhetorical Situation of Proposing is Defined by Risk

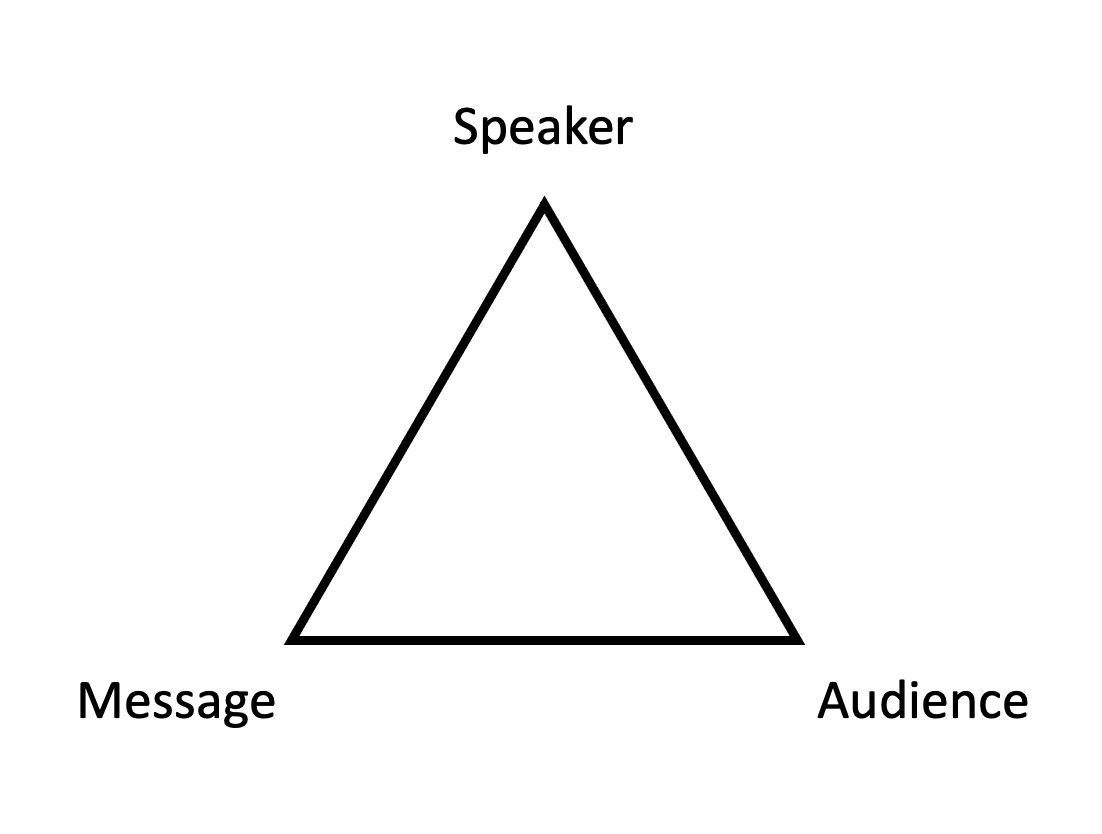

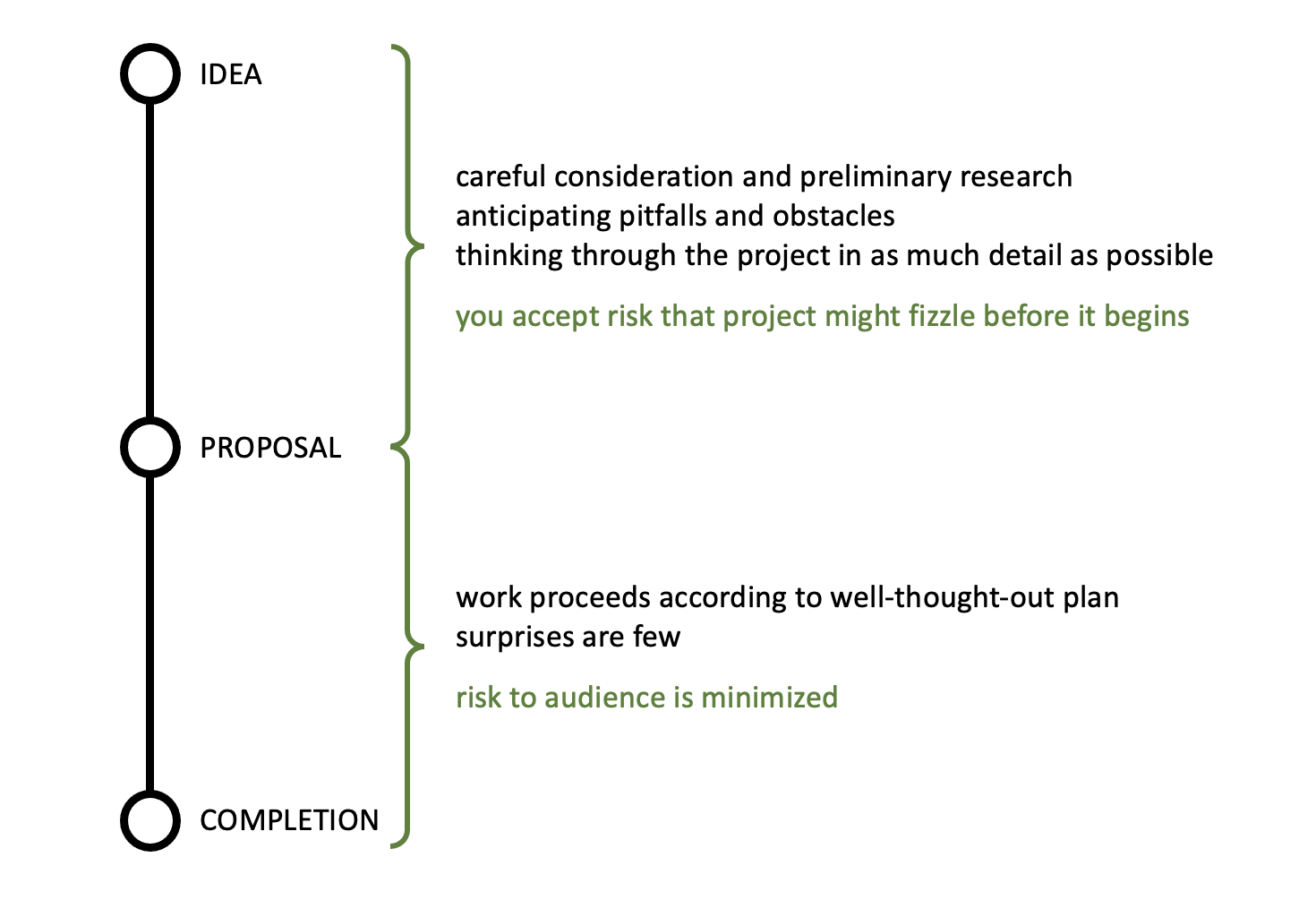

You’ve more than likely seen the following diagram at some point in your education:

This triangle represents a concept called the rhetorical situation. In simple terms, a rhetorical situation is one in which a speaker is attempting to get a desired response from an audience (this desired response is the purpose of the speaker’s message). For example, you (the speaker) may be trying to get your best friend (the audience) to loan you $20 (the message/desired response). That’s a rhetorical situation, and as such, it implies certain conditions of success—that is, the speaker will need to pitch their message in such-and-such a way if they are going to be successful getting that desired response from their audience.

An important note: Change any point of the triangle, and the conditions of success change along with it. For example, keep the speaker and the audience the same, but change the message from asking for $20 to asking for $200, or $2000, or $20,000, and it’s obvious that you’ll have to modify your approach in order to be successful. Or keep the speaker and message the same but shift the audience—you’re trying to borrow the money from a parent, or a sibling, or a complete stranger—and again the conditions of success shift.

The trick in any rhetorical situation is to understand the relationship between the three points of the triangle—especially to understand the audience’s needs, wants, worries, and interests—and then craft the delivery of the message with that understanding in mind.

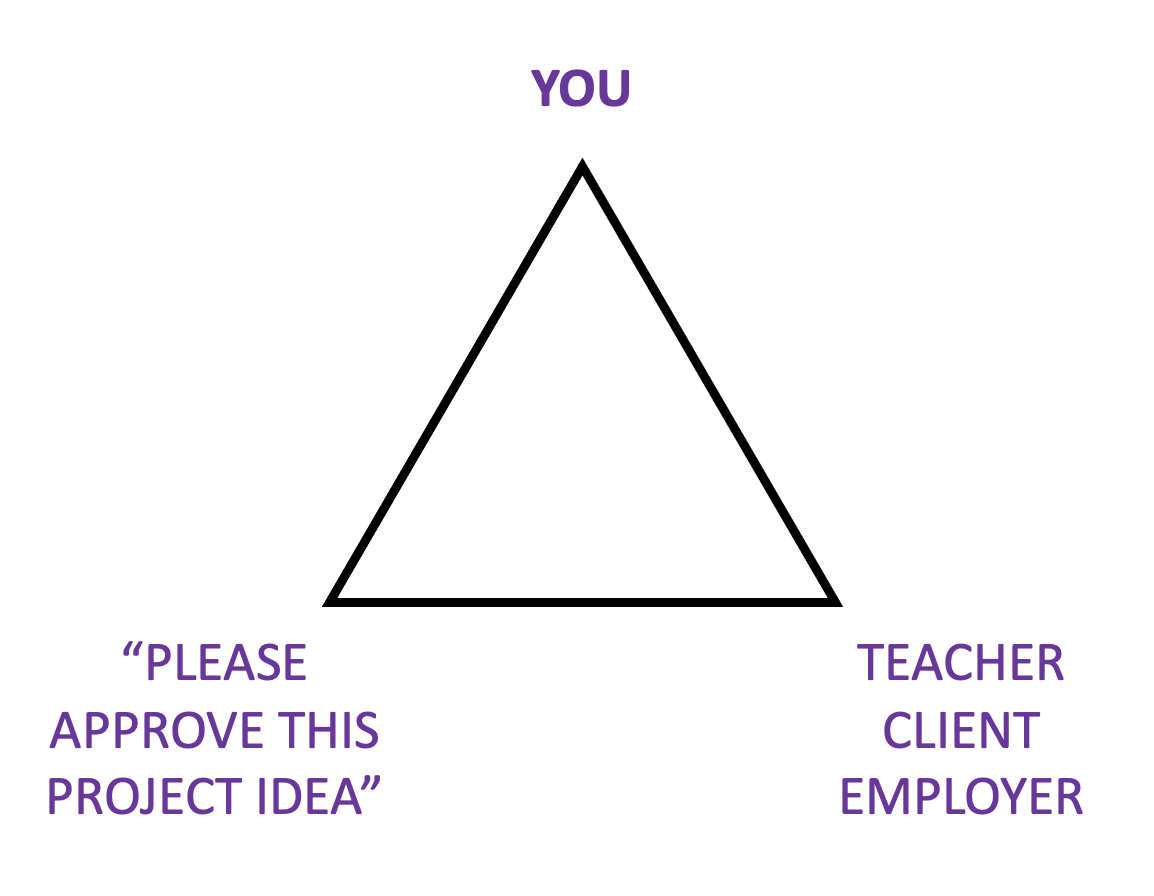

So what’s the rhetorical situation for a proposal? Well, you (or your team) are the speaker. That’s obvious. The audience is whomever you’re seeking approval (and possibly resources) from, and the message is “Please sign off on this project idea.”

Of course, these are broad generalities, and it’s the specifics of the nature of your project and the audience that will determine how you should best proceed. But there’s one thing you have to understand above all else, and it is this:

The proposed project represents risk for the audience.

Risk, you ask? What risk? Let’s explore what kinds of risk your audience might face using the example situations given at the top of the article.

The Mentor

If you are a student proposing a thesis or dissertation project idea to your academic mentor (that is, a professor), much of the risk they feel is on your behalf. They worry that you’ll start the project full of enthusiasm but will soon discover that the topic isn’t as easily researchable as you think. Yes, determining whether there are aliens at Area 51 is an interesting project, but it’ll be hard to prove one way or another when you lack the security clearance to access the facility or the records concerning it.

Or they worry that your project lacks a clear endpoint, that you’ll wind up writing and writing and writing—not just a thesis or a dissertation but some unfinishable magnum opus of indeterminate scope.

Or they worry that you’ll be unnecessarily duplicating research that’s already been done because you haven’t taken the time to actually familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge in the area of your interest. It would be quite a blow to discover, months into the project, that someone has already published more or less the exact thing you’re working on.

Or they worry that you might begin to jump to conclusions before collecting all the data, positing solutions to problems you don't fully understand yet.°

Of course your mentor wants to help you avoid those risks, but they also want to avoid risks they themselves are taking on in approving your project idea. If you don’t finish the project for any reason, they will have nothing to show for their investment of time and energy in you. Their reputation will not be improved (in fact, it may suffer), they may not get credit toward earning tenure or other professional accomplishments, and they will have been unable to mentor other students who might’ve been better equipped to succeed under their mentorship.

The Client

Let's imagine you work in advertising and are proposing an ad campaign idea to a client. In that case, the client shoulders most of the risk—after all, this ain’t school anymore; it's the cutthroat world of business, and the client isn’t there to hold your hand. The risks are largely the same as above, however. The client will be watching for red flags like these:

- A campaign without a carefully defined scope—for example, one that pitches Super Bowl commercials for a local restaurant

- A campaign that is merely a rehash of what other agencies have done for other clients

- A campaign that fronts ideas that aren’t based on careful research and analysis to identify the audiences, media, and approaches most likely to be affected positively by the ads

If any of these are present, there’s a good chance that the campaign will fail, and the client stands to lose time, money, and their reputation. Time, because they’ll have to start over months later with a new ad firm. Money, because not only are they paying you for your time and expertise and also for the cost of printing, broadcasting, and otherwise distributing the messages you create but also the revenue they will lose when the advertisements fail to generate the sales they were promised. And reputation, because a bad ad campaign can damage the image of the brand.°

The Employer

And finally, let's say you work in a corporation’s human resources department and want to reorganize the office travel approval process to make it more efficient and user-friendly both for the employees who use it and the HR personnel who administer it, so you ask your manager to approve your work on the project. That manager, as with the client above, takes on similar types of risk:

- If the project doesn’t have carefully defined boundaries, it might end up experiencing scope creep, or unintentional expansion of what the project aims to accomplish. For example, what started out as a reorganization of a travel approval process could expand to include all forms of employee reimbursement, or the adoption of new company-wide expense-tracking software, or even more.

- If the project doesn’t have a clear endpoint, you could end up working on it for weeks or months longer than originally agreed, and if the manager finally pulls the plug, there could be nothing to show for it.

- If the project attempts to solve a problem that doesn’t exist (or one that isn’t as big as you think it is), the solution could end up costing much more in time and resources than the problem ever did.

- Or, if the project tries to cover ground that was already covered by others at another time and place, committing resources to solve it again is a waste. Maybe others in HR already tried to streamline the travel approval process, only to find that the solution—the same one you will end up proposing—is unfeasible for any number of reasons. That’s two stones, no bird.

As with the client, your employer stands to lose time, money, and possibly their reputation. The salary you draw while you’re working on the project is a direct cost—that salary could’ve paid for you to work on something else during those weeks set aside to do the project. And if the project doesn’t result in increased efficiency, as you promised, then there is the indirect cost of time and money that could’ve been saved by all those who would've used the system you created. And your boss will have to account for these things to their boss, probably losing some degree of trust in their judgment.

See, regardless of the type of thing you might be proposing and your relationship to the person or group from whom you seek approval, there’s likely a large amount of risk involved for them. So what seems to you to be a chore—

Ugh, why do I have to jump through these hoops and write a timeline and a budget and an outline!?

—is, to your reader, the thing that helps them determine whether the risks are worth it:

It’s a great idea, but there’s no indication here of how long it will take, how much it’ll cost, or what the finished product will look like.

In other words, if you put your reader’s needs (for specificity and detail) before your own (to not have to think too hard about the future), your proposal will be that much more likely to elicit the desired effect.

How to Minimize Risk in a Proposal

Let’s use an analogy. Are you familiar with the popular The Price is Right game Plinko? In Plinko, contestants drop a puck into a matrix of pegs where it bounces at random until falling into a slot at the bottom marked with a prize.

Photo by CBS

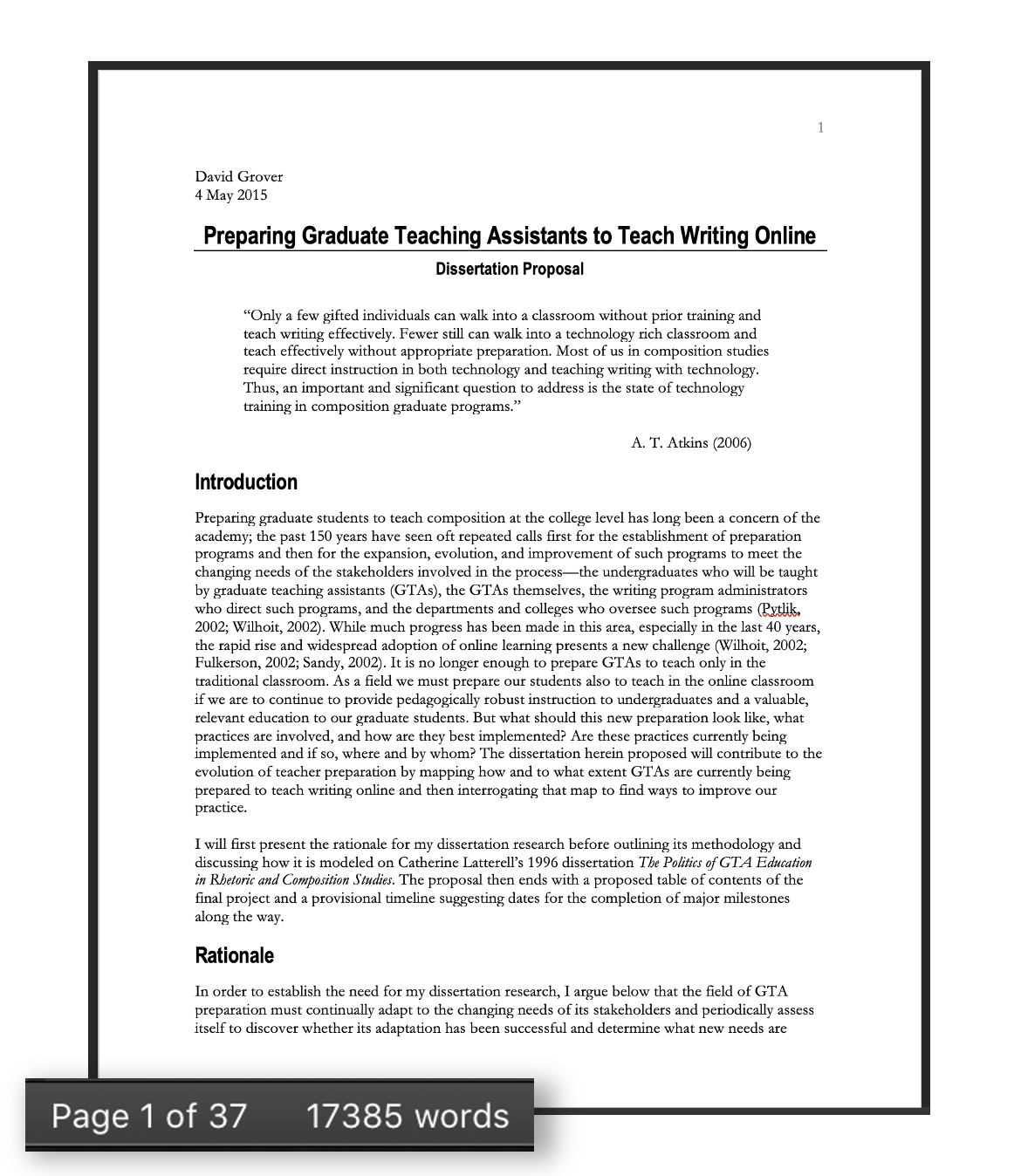

Working on a major project is sort of like playing Plinko—or it would be if the prizes were going to be shared with someone else, and that person was fronting the cost of you playing the game. Convincing that other person to pay your entry fee is like writing a proposal.

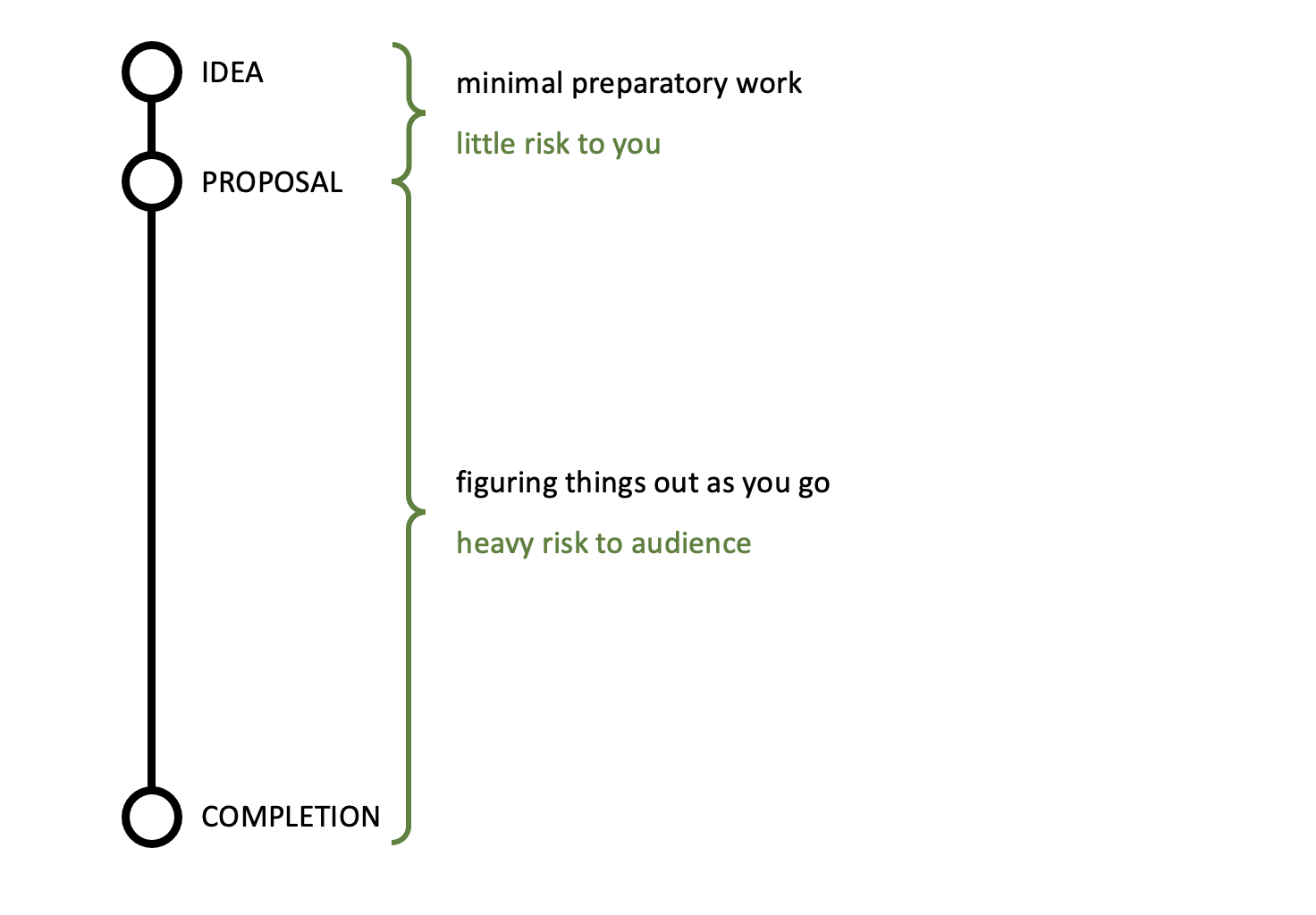

If your proposal is vague and light on details, that’s like playing Plinko from the top of the board.

A bad proposal doesn't do much preparatory work, leaving most of the risk to the reader.

The lack of specificity about the project's methods, timeline, precedent, budget, and other aspects mean there’s a real risk of the project going in an unexpected direction—just like how, once the puck falls, the laws of randomness can take over, and it can end up far from the big-win slot.

If, on the other hand, your proposal is detailed, specific, and comprehensive, that’s like playing Plinko but starting from lower down on the board. You specify exactly which slot you’ll release the puck into, and there’s a strong chance it’ll fall into the slot you’ve chosen. Of course there’s still an element of randomness involved, but the chances of things getting very far off track are minimized.°

There’s no shortcut to providing this amount of detail—you actually have to do the legwork. If the Plinko board’s height represents the project you hope to do, and you want to submit a proposal that shows the reader you’ll be dropping the puck from halfway down or farther, you have to more or less complete that portion of the project you hope to skip. In other words, by pushing ahead on your own before proposing, you take on some amount of the risk yourself so that you reader doesn’t have to.

A good proposal is the result of significant preparation, transferring a lot of the risk away from the reader.

Who Benefits: A Real-Life Tale

It may seem like I'm telling you to do a bunch of extra work so that your reader benefits.° But your reader isn't the only one who will benefit. You too will benefit as you embark on a project that is so much more well defined and impervious to screwballs and screwups. In minimizing the risk for your reader, you'll be minimizing the risk to yourself—the risk you were to excited about when your big idea hit to properly consider.

Allow me to illustrate with an example from my own life.

In September 2014 I completed my dissertation pre-proposal, a 19-page, single-spaced document almost 10,000 words long that detailed the research I intended to do to earn my doctorate degree. I thought this document was the bee’s knees, the most detailed plan I'd ever made for the most intense project I'd ever taken on. I was ready to begin!

But my dissertation committee—three professors who mentored me with incredible care—had other ideas. They sent me back to the drawing board, asking me to dig in so much deeper, researching everything I possibly could and thinking through every aspect of the project mentally before I committed to actually doing it.

In the end it took me nine months to finalize my proposal and get approval to begin the actual research.° This final draft—now a proposal rather than a preproposal—was almost twice as long as the original had been, citing 96 separate sources. I had completely rewritten the rationale for my research and revised the methods significantly.

You’d think I’d be angry at being held up for most of a year, but it was the best thing my committee could’ve done for me. In thinking through the project in such exquisite detail, I realized that what was originally intended to include three majors sites of study would work better with only two, reducing my research workload by a third and improving the coherence of my work at the same time.

Also, when I actually did start writing the dissertation, my proposal became most of chapters 2 and 3.° It gave me extreme confidence to begin with so much already written, and I was sure I could finish the project because no step was unplanned, no pitfall unanticipated. Believe it or not, the proposal was the hardest thing I’ve ever written in my life—much harder than the actual dissertation.

I’ll be forever grateful to my committee for recognizing the risks I couldn't see and forcing me to convince them that I had a clear plan. They didn’t want me to fail, to walk away from that huge investment in time and money with no degree in hand. And I didn't!°