Making a formal argument—whether it be for a research paper, an analytical business report, or some other purpose—requires you to do research in order to gather evidence to support your case. But what is evidence, what is its relationship to an argument, and what kinds of evidence might you look for? This article will explain it all.

How Arguments Work

In their simplest form, arguments are composed of three things: claims, reasons, and evidence. Let's discuss how they work together.

Every argument has a bottom line, a thesis—that thing the speaker is trying to persuade the reader to think, do, or believe. In arguments, we generally call this bottom line a claim to reflect their debatable nature. A claim is a statement with which a reasonable person can disagree; that’s what makes it something you need to persuade your audience about.

Statements of fact aren’t claims, usually, so they don’t make the basis of an argument. For example:

Applebee’s is an American restaurant chain

This is a fact, not a claim. It’s either true or not, and no amount of persuasion will make it true if it isn’t, and vice versa (persuasion may change whether or not you believe the fact, but it doesn’t actually change whether the fact is true). On the other hand,

We should eat at Applebee’s for lunch today

is a claim, a debatable statement. Reasonable people can disagree with it because it isn’t inherently true or false. It proposes a course of action, a “should” statement. It indicates how the speaker believes the world should be, not the way it is.

Because claims are debatable, they need to be supported if the audience is to be persuaded to accept them. The things we use to support claims in an argument are called reasons, and they are usually appended to the claim with a word like because.

We should eat at Applebee’s for lunch today because it is the best restaurant near here.

In many arguments, the reasons themselves are also debatable statements. We might call them sub-claims. Since they too are debatable, they need to be supported by something. While they can in turn be supported by other reasons (we could call these sub-reasons or sub-sub-claims), eventually we get to what we call evidence:

We should eat at Applebee’s for lunch today because it is the best restaurant near here. I know because I’ve tried them all.

Evidence often takes the form of facts, but it can also be opinions, logical statements, and a bunch of other stuff, as we’ll discuss below.°

Types of Evidence

After a couple decades in school, you might’ve been brainwashed to think that the only kind of evidence that works for school papers is scholarly sources. You know, the stuff you dig up in research journals by using library databases—a whole process that doesn’t make sense and that generally terrifies you.

And while it’s true that scholarly evidence is among the strongest type of evidence you can use, it’s far from the only type. I mean, it’s obvious. Every day you make and hear convincing arguments that use no scholarly evidence, don’t you? When you say, “Let’s have pizza for dinner,” or “Take the freeway; it’s faster,” or “I don’t think we should play tag in this spooky graveyard at midnight,” you are making arguments based not on research studies performed by scientists somewhere but on other types of evidence. We’ll actually be discussing several common types of evidence and the situations in which it is appropriate to use each kind:

Evidence from Yourself

- Personal experience

- Personal observation

Evidence from Others

- Testimonial

- Expert opinion

Evidence from the World

- Case example

- Research study

Evidence from Logic

- Thought experiments

- Hypothetical situations

- Syllogisms

- Analogy

Think of Your Audience

Before we jump into the types of evidence, let’s lay down the ground rule of how to determine whether a type of evidence is right for the argument you’re making. Ready? It’s this:

The right type of evidence is the type that your audience finds convincing.

That’s it. That’s all. There’s no complex mathematical formula to determine when you should use a testimonial and when you must use a research study. It just comes down to whether your audience will find the evidence you present credible and convincing.

Evidence from Yourself

This category of evidence concerns things you know or believe based on your own experience of the universe.

Personal experience includes things you have, uh, personally experienced. Like, if you’re a cancer survivor, or a Catholic, or an Olympic gold medalist, you have direct experience with those things and can say something about them, and people tend to listen to you more than if you have no experience with the thing you’re talking about.

Personal observation includes things you’ve seen but haven’t directly lived through. I might be married to a cancer survivor, or have attended a Catholic private school (though I’m not Catholic myself), or I may have attended an Olympic event where a gold medal was won. Having observed these things gives some strength to my words when I talk about what I saw—more, at least, than if I cannot claim to have ever seen what I’m talking about.

These are some of the most common types of evidence we use because we have instant access to it since it is from our own lives. Think about it: how often do you begin a sentence with the words “As a computer science major…” or “As someone who grew up with four sisters” or “As a major fan of Radiohead who owns and has memorized every song on every album…”? That’s you prefacing your evidence by saying where it comes from.

The main strength of these kinds of evidence is that they are real and personal. When you talk about yourself, you tend to invoke both pathos and ethos—pathos because any personal story is sure to have an emotional connection, and ethos because audiences inherently trust that you know what you’re talking about.

One main weakness is that there is little protection against bias, or the tendency to interpret things how one wants to see them rather than how they objectively are. When I told people I was moving to Kansas City, I heard a lot of “Oh, I grew up there—KC is the best, nicest, most beautiful town in America.” While these people were speaking from personal experience, I took their comments with a grain of salt, knowing that people tend to be biased in favor of their hometowns. Odd that not one of them mentioned KC’s very high rate of gun violence and its problematic racial and economic divide along Troost Ave.

The other weakness of personal evidence is that it is susceptible to a logical fallacy called a hasty generalization. A hasty generalization is when we take a few instances of something and incorrectly assume that it must be generally true across the entirety of that thing. When you say, “Don’t eat at the Applebee’s on Main St.—I had a bad experience there,” you’re implying that, generalizing from your one bad experience, all or most eating experiences there will be bad, which is of course ridiculous. An Olympic gold medalist cannot speak on behalf of all gold medalists, nor can a single Catholic speak for all Catholics. And even if I closely observed a loved one fight cancer, I cannot claim that the experience was representative of all cancer fights.

Personal experience and observation, therefore, work best when they are applied to small, specific situations and carefully avoid the appearance of bias and hasty generalizations.

Evidence from Others

You are not the only one who has personal experiences and observations that can work as evidence—everyone around you is a potential source of experience and observation, and you can use that as evidence too. This can be very convenient if someone other than yourself is a better placed source—this is what journalists do all the time when they rush to the scene of a happening and interview eyewitnesses to include in their newspaper article or local news broadcast.

Unfortunately, such evidence is subject to the same weaknesses as personal evidence—other people, just like you, are subject to bias and generalizing.

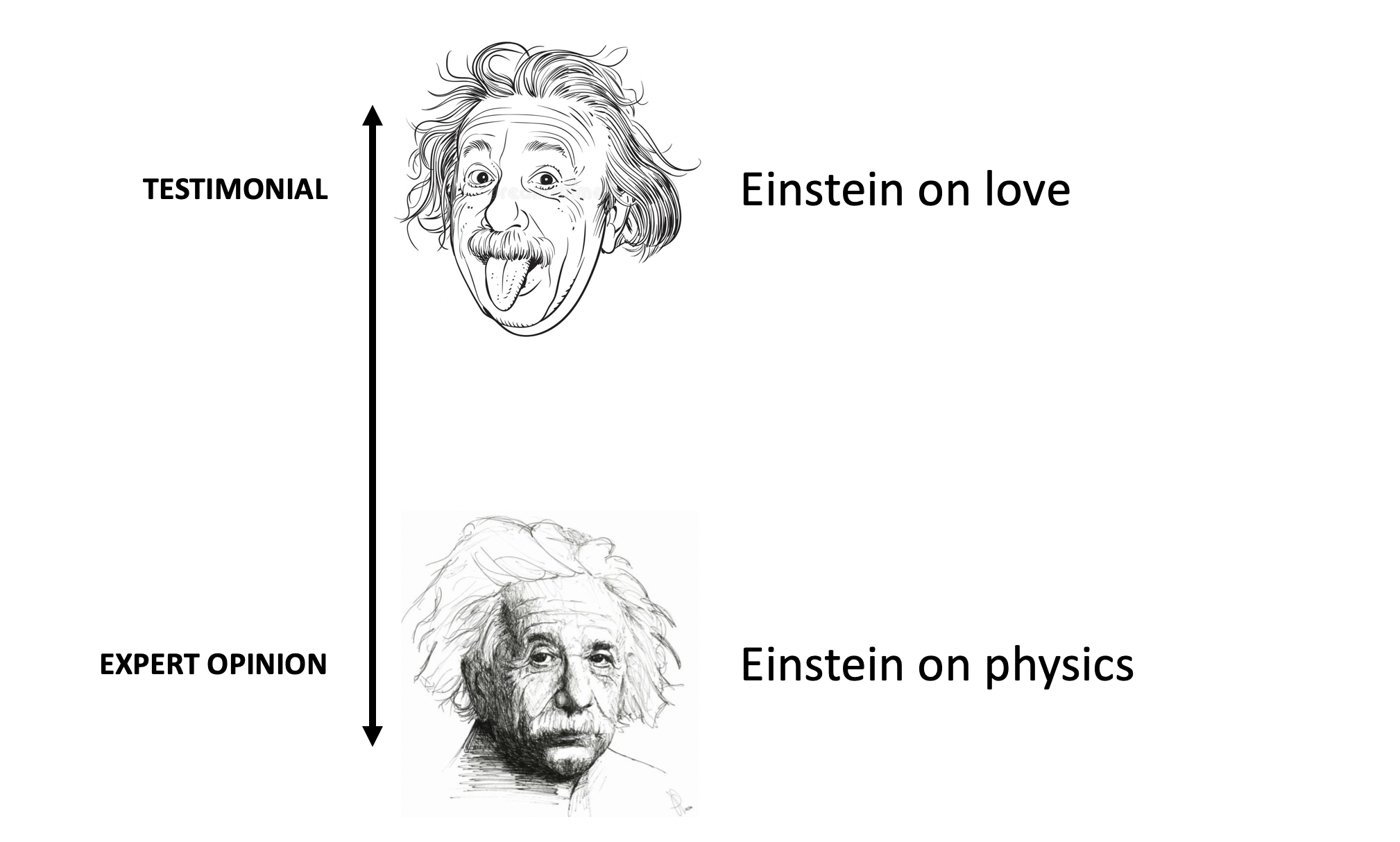

We typically call other people’s experiences and observations testimonials. When Michael Jordan talks about how much he likes Hanes underwear, or Kylie Jenner praises a product on her Instagram feed, what we’re seeing is a testimonial. And when you think about it like that, another weakness becomes apparent: conflict of interest. Can we really be sure that Michael Jordan and Kylie Jenner personally use and love the products they are talking so fondly about—or could the money they receive in return for their “promotional consideration” have something to do with it?

What if Michael Jordan isn’t talking about underwear? What if he’s talking about the best way to coach a basketball team or why he thinks a certain NBA team will definitely make the playoffs next year? Is that still a testimonial?

See, MJ isn’t an underwear scientist or anything—he doesn’t really know more about underwear than you or me, so his opinion about Hanes over Fruit of the Loom isn’t really very compelling evidence. But he is one of the preeminent basketball players of all time, a recognized expert in the field. When he is talking about something he is an expert in, we don’t call it a testimonial; we call that expert opinion.

But it’s important to recognize that a testimonial and an expert opinion aren’t really different things—they are both largely based on personal observation and experience. So rather than think of these as completely different kinds of evidence, let’s think of them existing on separate ends of a spectrum. The more experience and expertise a source has with the topic they are opining on, the more we can call their evidence an expert opinion. The less experience and expertise, the more it is a mere testimonial.°

Obviously expert opinion is more believable than testimonial is in most situations. Being an expert addresses the weaknesses of bias, hasty generalization, and conflict of interest to some degree, turning them to strengths. This is why news programs so often invite scientists, university professors, think tank researchers, politicians, and other professionals on to comment on the day’s news. It’s why kids say to their parents, “But my teacher says we have to do math this way!”

But expert opinion doesn’t completely solve these weaknesses. After all, not all experts agree, and they can’t all be right.

Evidence from the World

Not all evidence comes straight out of one individual’s lived experience. In fact, two of the strongest kinds of evidence—case examples and research studies—deliberately avoid relying on single sources.

Case examples are real-world occurrences that are similar enough to the issue at hand that they can be used as convincing comparisons. For example, whenever we debate universal healthcare in America, we use other countries that have universal healthcare as case examples to show how such a system might work in America. Or, if you’re arguing that your university should offer student free parking and bus passes, you could provide details about other universities that have done so and what the outcomes have been.

One strength of a case example is in how it argues by analogy. Argument by analogy is when you show that because two things are similar in some respects, they are likely to be similar in other respects, as the examples in the previous paragraph do. Most people find a strong analogy to be highly convincing and logical.

Another strength is how case examples can be grounded in a well-documented, verifiable reality. When we’re talking about personal experience and testimonials, we’re relying on the senses of a single person to accurately represent reality, which is why bias is such a problem. But if we’re using an entire school, program, city, or country as our touchstone for representing reality, that’s more convincing and less susceptible to bias, especially if the picture we paint is based on carefully gathered statistics or other documented sources like research studies, which we’ll discuss below.

The primary weakness of a case study is that it is hard to create an airtight analogy. Sure, Finland may have universal healthcare and it may be going great—Finland keeps ranking top on that “Happiest Countries” study that comes out every year—but Finland is unlike America in many demonstrable ways including the demographic makeup of the country, the political and economic systems, and so on. A strong case study has to account for such differences lest an opponent point them out and undermine our argument.

Research studies are scholarly or professional projects that use commonly recognized research methods to generate their results and that are published professionally in some way.

Typically, a scholar or professional researcher in the sciences and humanities will first review existing research to determine what is known and unknown about a topic, then generate a research question meant to push human knowledge a little further than it has gone before. Next they will design their study, employing a methodology appropriate to the question and area of study. Then they use their methods to gather and analyze data, which is used to answer their research question.

Research methods vary widely across fields. For example:

- A physicist or a chemist might set up a lab experiment to determine the outcome of smashing particles together or mixing certain elements in certain conditions (these are often called quantitative methods).

- Similarly, a medical researcher or biologist could set up a controlled experiment in which half the test subjects receive a medicine while the other half receive a placebo, then measure the results (also quantitative).

- An accounting researcher could examine the results of dozens of existing accounting studies to determine if there is a trend of burn-out among early-career accountants right after the busy tax season (this is called a meta-analysis).

- A psychologist or sociologist could gather interviews with PTSD sufferers and code the transcripts for key words and concepts, searching for trends across victims of both war and natural disasters (these are types of qualitative research).

- An anthropologist could embed herself with a tribe of aborigines (or high school sophomores) and conduct an ethnography of the social mores exhibited among the group (another qualitative method).

- A historian could examine letters from Civil War soldiers to their families, looking for evidence of what the soldiers believed the cause of the war was (this is a form of textual research).

- A literature scholar could reinterpret Shakespeare’s Hamlet through an LGBTQ lens, examining how modern conceptions of gender and sexuality alter key relationships and reveal new meanings (this can be called critical analysis).

It’s important to recognize that no field uses a single method—all available methods are widely shared, often mixed, and further developed by many fields. Research doesn’t just mean numbers or statistics, either, though many forms of research rely heavily on statistical analysis.

The main strength of research studies is that they come closer than other evidences to solving the problems of bias, hasty generalization, and conflict of interest. Research methods are almost all designed to minimize the impact of the researcher and maximize the purity of the data and interpretation. The scientific method, for example, recognizes that humans are an inconsistent and untrustworthy bunch, so it fights back by ensuring data is gathered and analyzed in ways that can be replicated by other people in other places and other times—but getting the same results.

Many research studies are scholarly, meaning they are performed and published by university professors and other academics. Academics are often protected by tenure—meaning they can’t be fired for researching something or publishing results their employer doesn’t like—and they rarely stand to gain financially from their research (publishing in academic journals doesn’t pay any money, for one thing), so they tend to have fewer conflicts of interest than other sources. Compare this to a researcher hired by, say, the Avocado Growers Association to research the health benefits of avocados. The researcher may feel pressure to find only good things about avocados lest he or she be out of a job, while a university professor can publish whatever he or she wants about avocados with no danger of unemployment.

Another reason research studies are seen as strong evidence is that many of them are published in peer-reviewed journals or are otherwise peer reviewed before publication. Here’s what that means. If the avocado researcher wants to publish his or her study in the peer-reviewed journal Avocado Research, the editors of the journal will first send the paper to at least two reviewers. These reviewers have PhDs in the field of study represented by the journal and are recognized as experts in the field. The reviewers examine the methods and results of the study to determine whether the study meets the standards of research in that field, and only if it does can the paper be published. The reviewers don’t know who wrote the paper, and the writer doesn’t know who reviewed the paper, so there’s no bias based on personal relationships or rivalries. Also, because the journal itself is sponsored by a university rather than a for-profit business, no one stands to make any money on the publication.

Not all research studies are scholarly, nor are they published in academic journals. Many researchers—including doctors, engineers, economists, and more—work for the government, think tanks, and private and public corporations. Their work may be published in industry journals, as white papers, or in government reports. While such publications don’t have the same exact credibility as peer-reviewed scholarly journals, they are often highly credible and can have excellent reputations.

What are the weaknesses of research studies? Well, the main one is finding them. It can be quite difficult to find exactly the right study that proves a point you want to make—assuming such a study exists at all. Since most research is published in scholarly and industry journals, it isn’t typically the type of thing you can just Google for. Instead, dedicated databases and search engines—like EBSCO Host, Lexis Nexis, ProQuest, and JSTOR—are typically used to find and access research studies.

There’s also the difficulty of reading research studies. They are typically written by experts for experts, so they can be dense with technical jargon and complex concepts. Luckily, many journal articles follow the IMRAD structure (Intro, Methods, Results, and Discussion), making it easy to know where to focus one’s reading—usually the intro and discussion sections are a good place to start, as they tend to focus on big pictures and usable takeaways. Journal articles also typically have an abstract (or summary) that can be a shortcut to comprehension.

Lastly, you should be wary of how much you rely on statistics taken from research studies. Audiences often treat statistics with suspicion—and for good reason. It’s easy to make statistics say whatever one wants them to say by being choosy about what data is and isn’t shared as well as how it is framed. For example, a poll might put one presidential candidate ahead of another by 7 percentage points, conveniently leaving out that the margin of error is plus or minus 3 points. If the lower candidate’s score came in 3 points low and the higher candidate’s score 3 point high (both within the margin of error), the actual difference between their chances could be as little as a single point. There are dozens more ways statistics can be misleading, but going through them is beyond the scope of this article.

Evidence from Logic

The last kind of evidence isn’t based on the sensory experiences of you, your peers, or scientists. It’s evidence based on pure reasoning or logic. Sometimes all you have to do to convince someone to accept your argument is to explain in a logical manner why the thing you’re arguing is a reasonable proposition (or course, more often you have to do that in addition to providing other kinds of evidence). Some common types of logical evidence are thought experiments, hypothetical situations, syllogisms, and analogies—though just explaining things is good too.

In the following example, philosopher Peter Singer, writing in the New York Times, using a thought experiment to argue for our obligation to engage in charitable giving:

In an article I wrote more than three decades ago, at the time of a humanitarian emergency in what is now Bangladesh, I used the example of walking by a shallow pond and seeing a small child who has fallen in and appears to be in danger of drowning. Even though we did nothing to cause the child to fall into the pond, almost everyone agrees that if we can save the child at minimal inconvenience or trouble to ourselves, we ought to do so. Anything else would be callous, indecent and, in a word, wrong. The fact that in rescuing the child we may, for example, ruin a new pair of shoes is not a good reason for allowing the child to drown. Similarly if for the cost of a pair of shoes we can contribute to a health program in a developing country that stands a good chance of saving the life of a child, we ought to do so.

—Peter Singer, "What Should a Billionaire

Give – and What Should You?"

The strength of this type of evidence is that good logic is hard to argue with, as it transcends this mortal coil with all its biases and conflicts of interest.

One weakness is that there is a long list of logical fallacies out there, and it can be hard to create a logical argument that doesn’t fall prey to one of them. Another weakness is that audience’s might dismiss pure reason as being too divorced from the real world and its complexities. You may show that universal healthcare is a natural right of humanity, but your opponent might sink your argument by asking, “How will we pay for it?” Best to combine logic with the other types of evidence to build a stronger argument overall.

Think of Your Audience Again

Recall what I said at the beginning of this section on types of evidence:

The right type of evidence is the type that your audience finds convincing.

Consider also this fine distinction: the point of persuasion isn’t to prove that you’re right—it’s to convince your audience to accept your claim. Proof is elusive; it is almost unattainable by humans due to the limitations of how we sense and experience reality. In our everyday arguments about the best course of action to address a problem, we aren’t looking for absolute proof that the solution will work. We just need convincing that the solution is worth trying, that it’s better than the other available options. We know life is messy and that no solution will entirely solve a problem on its own. We accept a little wiggle room, a little chance.

So as you consider how you can convince your reader that your claim is acceptable, remember to afford them the same humanity. Consider what they will be convinced by and what won’t go over so well. Preschoolers don’t have any patience for scholarly stuff, and a Fox News devotee might not value a CNN source as much as you do (or vice versa).

Putting an Argument Together

Claims, reasons, and evidence: these are the three main parts of an argument. Once you understand this, you’ll start to see arguments all around you. With practice, you can start to take the arguments apart, look at their individual parts, and evaluate where they are strong and where they are weak. You can even begin to make your own arguments stronger. Let me give you two examples.

Example 1: Five-Paragraph Essay

You know what a five-paragraph essay is: an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Another way to think of it is that the paper

- States its claim and previews the reasons

- Explains the first reason and presents evidence

- Explains the second reason and presents evidence

- Explains the third reason and presents evidence

- Restates the claim and reviews the main reasons

Example 2: A Murder Trial

Now let’s imagine we’re prosecutors in a courtroom, and our job is to prove that the defendant killed someone. Now, I’ve watched a lot of legal dramas, so I know that in order to convict a murderer, you have to show they had the means, motive, and opportunity to do the deed. So we might structure our case along those lines:

- Opening Statement

- We explain to the jury that we will show the defendant is guilty (this is our claim) by proving he had the means, motive, and opportunity to do it (these are our main supporting reasons).

- Means: Was he capable of committing the crime?

- We call the defendant’s roommate to the stand; he testifies that the defendant is left handed and lifts weights four times a week.

- We call the forensics team leader to the stand; he testifies that the murder was committed by a knife held in the left hand by a very strong individual at least 6-foot-2, as evidenced by the position and depth of the stab wound.

- We submit into evidence the arrest report, which shows the defendant is 6-foot-4.

- Motive: Did he want to murder the victim?

- We submit into evidence the phone records and social media accounts of the defendant, wherein he expressed extreme anger with the victim on multiple occasions and made credible threats.

- We call the victim’s girlfriend to the stand; she recounts two verbal altercations between the victim and the defendant.

- Opportunity: Did he have the chance to use the means to complete his motive?

- We submit into evidence cell phone GPS tracking and CCTV footage, which put the defendant at the scene of the crime when the crime was known to happen.

- We submit into evidence the murder weapon, which the roommate swore in an affidavit belongs to the defendant.

- We call the arresting officer to the stand; she recounts how the defendant was found at the scene, holding the weapon next to the victim’s body.

- Closing Statement

- We review for the jury the main points of our case and most convincing evidences.

Whoa, that got thrilling…and a bit gruesome. But that’s how it’s done. Prosecutors line up claims, reasons, and evidence to make their case. Not only that, though, because the defense attorneys make the opposite argument at the exact same time. Their claim is that the defendant is either innocent or must be found not guilty because either there is no means, motive, or opportunity or a lack of evidence means there is reasonable doubt. Whenever the prosecution examines a witness, the defense then gets to cross-examine the witness to point out weaknesses in their evidence.

It’s dueling arguments in real time!

Also, did you notice how this wasn’t really any different from the five-paragraph essay? Only instead of five paragraphs we expanded the body into five sections, each with multiple pieces of evidence. Cool, right?

Conclusion

I hope this article clarified for you what evidence is and how it is used in the context of an argument. Understanding what evidence is is crucial to performing research—otherwise, you don't know what it is you're looking for when you research.