If you are a student, it is likely you’ve spent almost all of your writing life focusing on academic writing of various kinds—research papers, analyses, reports, essays, etc. But unless you intend to stay in academia, a day will soon arrive when you just won’t write like that anymore. And if you, like so many of your peers, soon find yourself working in some professional setting (that is, the world of offices and business and government and nonprofits and all the other types of work we generally call “white collar”), you’ll encounter a host of new types of writing—emails, memos, letters, resumes, proposals, reports, and so on.

The bad news is that you probably won’t like these new, professional forms of writing any more than you like the old, academic ones. Writing is, to put it bluntly, damned hard to do well, regardless of the setting.

The good news, however, is that much of what you’ve learned about writing for school and teachers will serve you well when writing for offices, clients, customers, and colleagues. Regardless of setting, readers generally want clear, concise writing that conveys an intelligent and well-developed message.

In this article, I want to offer you a big-picture view of professional communication that can help you make the mental shift from academic writing to professional writing. I’ll start by presenting and discussing two broad concepts, rhetoric and genre, and how they apply to professional communication. I’ll then clarify the relationship between them by presenting you with the Golden Rule of Professional Communication, a principle that will help you make good writing choices long after you leave school.

Rhetoric

Let’s start by talking about a concept called rhetoric. Rhetoric is often associated with the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, who defined rhetoric as “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion”—teachers often shorten this to “the art of persuasion.” Simply put, to Aristotle, rhetoric is the ability to discover and then make an argument, to persuade your listener to agree with you on a debatable topic. Should Athens go to war with Sparta? Should we have pizza for dinner? Should you major in journalism? These are questions that rhetoric is designed to answer, first by helping you consider “the available means of persuasion” to inform your decision and then by helping you convince others that you are right.

In the years since Aristotle first set down his ideas of what rhetoric is and how it works, we’ve expanded the idea somewhat. Whereas Aristotle was mostly thinking of how Athenian men made arguments in the form of formal public speeches, modern thinkers tend to consider all communication—both verbal and nonverbal, written, spoken, and otherwise—to be rhetorical in nature. Not all communication is persuasive (some is intended to merely entertain or inform, for example), so a more expansive definition is warranted. Let’s, therefore, define rhetoric this way:

Rhetoric: the art of using communication to get a desired response

If you think about it, we all use rhetoric more or less constantly, in all sorts of conscious and unconscious ways, as we interact with other people each day of our lives. A baby crying is rhetorical in that it seeks to inspire a certain response from a caregiver—to be fed or changed or lulled to sleep. Putting on nice clothes for a job interview is rhetorical in that it seeks to convey a level of professionalism and trustworthiness, in hopes of inspiring the interviewer to offer a job. Posting to social media is rhetorical in that it seeks to inspire likes, comments, and other interactions.

Rhetorical Situations, Conditions of Success

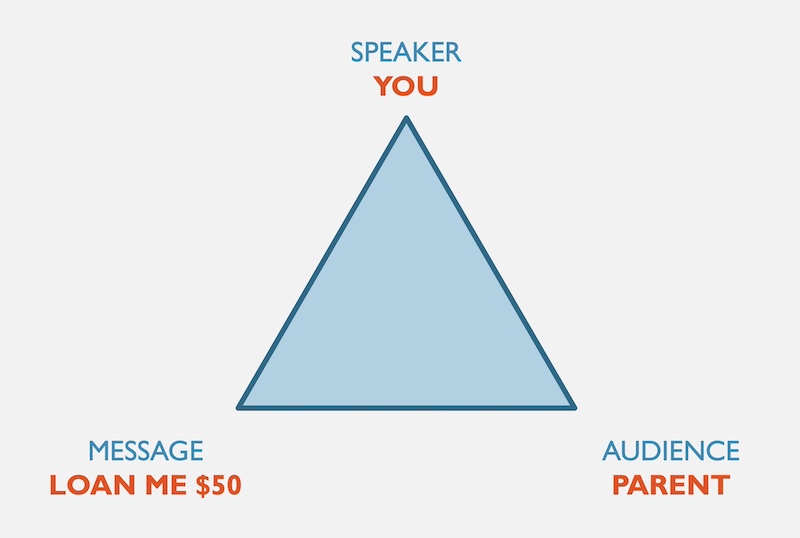

In any communication situation, there is always, at the very least, a speaker, an audience, and a message being conveyed. We call this the rhetorical situation, and we often represent it using a triangle. For example, let’s define the rhetorical situation of needing to borrow $50 from your parent, guardian, or other trusted adult:

In this situation, you are the speaker, your parent or trusted adult is the audience, and the message is the desired response you hope your audience gives you—loaning you $50. In order to get that desired response, however, you’ll have to present yourself and your message in a way that is persuasive to your audience; let’s call this the “conditions of success.”

Now, because you’ve been using rhetoric your whole life, and because you likely know your parental figure quite well, you probably already intuitively know the best way to approach this rhetorical situation, the best way to meet the conditions of success. Maybe your mom is a real softy, and you usually succeed by playing up the familial bonds you share:

Mother dearest, do you remember the day I was born, when you first held me in your arms and thought that you’d never been so happy before and couldn’t imagine being so happy again? I need you to keep that in mind as I ask you to loan me $50…

Or maybe your dad is best approached from an angle of responsibility and accountability:

Dad, I know how much you appreciate straightforward talk and accepting responsibility, so I’ll just come out and say it: I made a mistake and now I need to borrow $50…

When you choose which person to ask and when you tailor your message to that person, you are using rhetoric. By accurately predicting the conditions of success created by the specific rhetorical situation you find yourself in, you optimize your chances of getting the desired response you are looking for.

Ever-Shifting Situations

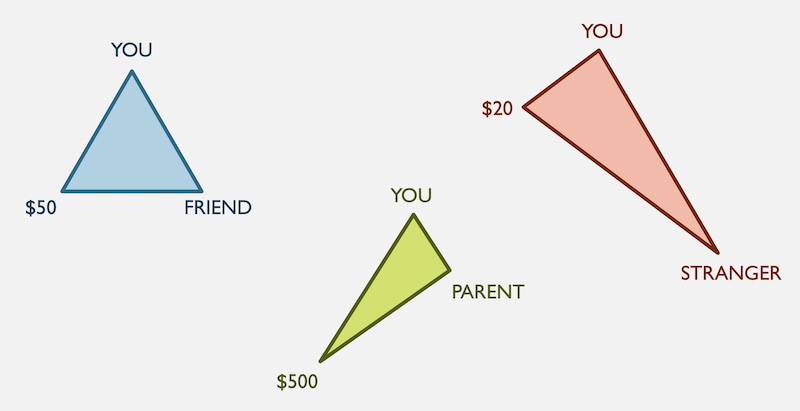

But here’s a key truth to rhetorical situations: change any part of the triangle, and the situation shifts, as do the conditions of success. Imagine for a moment that it’s still you speaking to, say, your mom, but the amount of money you need to borrow changes. Instead of $50, it’s $500, or $5,000, or $50,000. Increasing the amount changes the rhetorical situation by dramatically changing the size of the ask and the stakes for your audience. What was a simple request might now be a big ask, requiring detailed reasoning to justify to your audience why you need the money and how you propose to pay it back.

Or let’s keep the message and the speaker the same but change the audience—instead of asking your mother, let’s say you are asking your best friend, or a neighbor, or your ex:

- Your best friend may trust you to the same degree as your mother but have less access to the cash, so you might need to emphasize how quickly you’ll be able to repay.

- Your neighbor may need reassuring both that they can trust you and that you’ll pay it back on time.

- Your ex…well, sometimes the conditions of success are too steep, and you know that no approach to the rhetorical situation is likely to succeed.

We can even change the speaker. You could ask your mother for $50, but is that the same as if your brother or sister (or some other relation) does it? Would they approach the situation in the exact same way you would?°

It can be helpful to visualize these shifts in rhetorical situation as a change in the shape of the triangle. We might imagine the sides growing longer as the stakes grow higher and the relationships between the speaker, audience, and message to grow more tenuous.

However you want to imagine it, just keep in mind these core ideas:

- Every rhetorical situation is different and has its own unique conditions of success you need to meet in order to get the desired response.

- Smart rhetoric always orients itself to the audience, anticipating their needs and desires.

Rhetoric in the Professional World

In the real world, and especially the professional working world, rhetorical situations are often complex or unfamiliar. It’s one thing when you are communicating with people you’ve known your whole life, but quite a different one when communicating with strangers or with groups of people, each with slightly different needs. Let’s look at some examples.

Say you are applying for a job. Chances are that you’ve never met the people who will read your resume and cover letter, so how can you figure out what the conditions of success are, how can you anticipate your readers’ needs to make sure you accommodate them?

Or say you are applying for a business loan to fund building and opening a snow cone stand. When it was $50 from your mom, you knew how to appear trustworthy enough to warrant the loan—but now we’re talking about thousands of dollars, loaned with interest, from a bank. How can you show the loan officer that your scheme is a safe bet, that you’ll be able to pay back the loan, plus interest, as your business grows?

Or let’s imagine you have a job in a business environment, and your manager asks you to compose a detailed report about a project your team has been working on for the past few months. A lot of different people might read this report, each with a different need or purpose in mind:

- Your manager may use it to evaluate your writing ability to judge whether to trust you with similar work in the future.

- Your teammates want to see their work on the project accurately represented and may use the report when arguing for promotions, raises, or new positions.

- The executive leadership of the company may use it to evaluate the success of your team or your manager, to make decisions about future company policy or strategy, or to tout the company’s success to board members or investors.

- Other teams and departments in the company may use it in their work—for example, the accounting department may use parts of it in their own budgeting or fiscal reporting, and other teams may use it as a model for their own work or reports.

- External clients or customers may even read it as they are considering whether to do business with your company.

This potential tangle of rhetorical situations threatens to be overwhelming because each potential audience—whom you may or may not know personally and who has various degrees of power over you—has their own set of needs, which you may or may not be able to predict. How can you possibly accommodate all these audiences’ needs to ensure you meet the condition of success for each individual rhetorical situation?

Genre to the Rescue

As you can see, in professional communication, the stakes can be very high and situations can be very complex, making it difficult for even the most skilled communicators to succeed. However, to combat this, we have a useful tool at our command: Genre.

A genre is a type or category of a thing. In film, for example, we often see the genres of action, thriller, horror, romantic comedy, and so on. Such standard, recognizable categories help audiences by giving them an idea of what to expect from a movie. For example, if you know you are going to see a horror movie, you know what to expect (jump scares, monsters, mortal danger, creepy music) and what not to expect (choreographed dance numbers, meet cutes, a high volume of jokes). These expectations are useful in all sorts of ways:

- When choosing what to watch, you probably almost always start by identifying the genre you are in the mood for.

- You orient yourself toward the film as it rolls by putting up your defenses (for horror), by opening your heart (for romance), by suspending your disbelief (for fantasy and sci-fi), etc.

- When describing a film to someone else, you use its genre as a shortcut to help your listener understand your description.

- When evaluating how much you liked a film, you probably judge it against the standards of its particular genre—after all, you wouldn’t judge a comedy on how scary it was or a horror film on how funny it was.

But genre is also useful for writers. Imagine you are a screenwriter. If you sit down at your computer to write a new film, you might be overwhelmed at the wide-open possibilities before you. But if you start by narrowing down to a specific genre, suddenly the possibilities collapse to a more manageable scope. If you decide to write, say, a spy thriller, then you can start to make some assumptions about what your audience is expecting,° which helps you begin to figure out ways to meet or even exceed those expectations.

Genre in Professional Communication

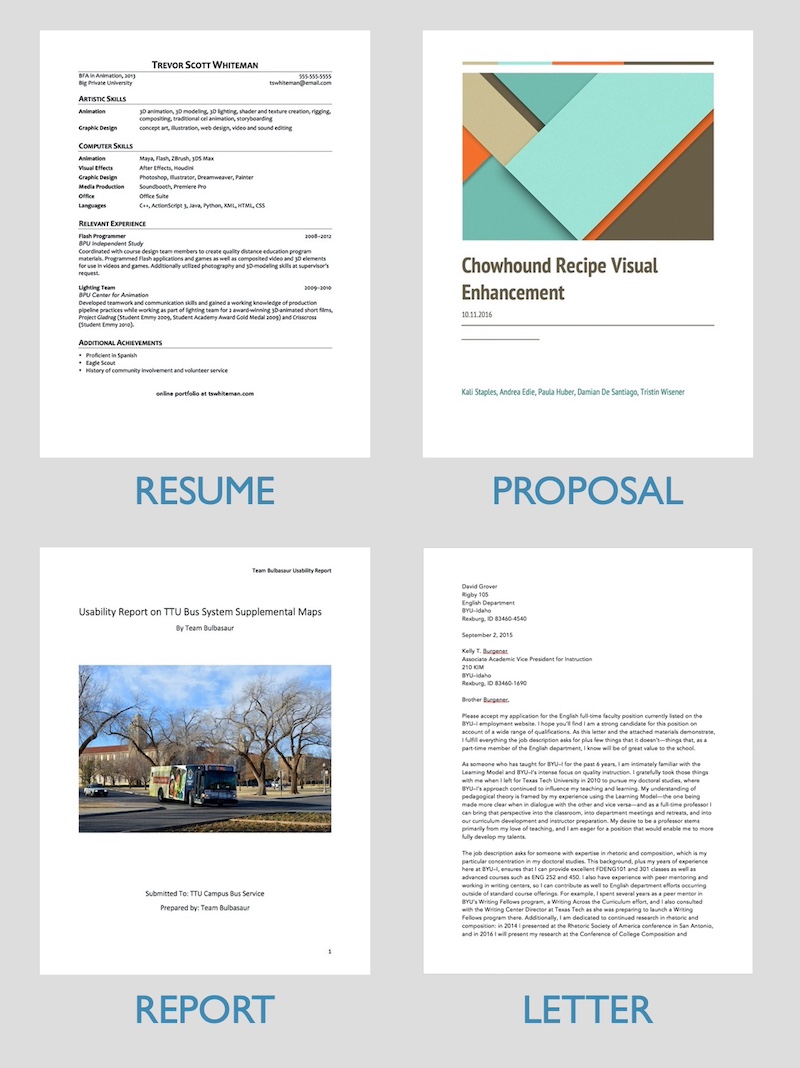

Let’s turn back to professional communication. There, we also have genres, such as letters, memos, emails, resumes, presentations, proposals, reports, and so on. Each genre has its own conventions determining what types of content and format are typically used and not used, and these conventions help both readers and writers quickly and consistently navigate complex or unfamiliar rhetorical situations.

Let’s return to our examples from above and see how genre can help you navigate them.

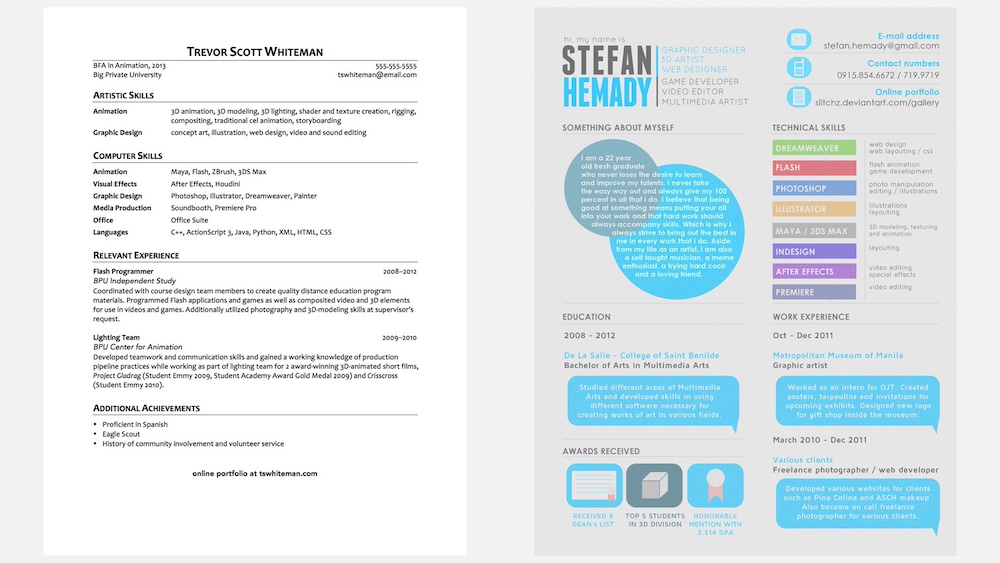

When applying for a job, you may never have met the people who will review your application, but they likely followed the genre conventions guiding the construction of the job ad in order to give you some idea of what they are looking for. And you can follow the genre conventions for resumes, which tell you what kind of information you should include (name, contact info, education, work history, skills, achievements, etc.) and also how best to format that information for your reader.

When applying for a business loan, you can rely on the business plan genre to anticipate what the bank will want to know about your snow cone stand and what order to present the information. By including all the standard parts in order, you make it easy for the bank to evaluate the risk of loaning you the money, and by formatting the plan in a professional way, you put your best foot forward, like wearing a fancy suit to a job interview.

Or take the report that needs to serve so many different audiences. The genre conventions that guide the writing of reports help you accommodate all your different audiences:

- An executive summary at the beginning helps the company leadership, whose time is precious and who may not need all the nitty-gritty details, understand the big picture of the report quickly.

- A table of contents helps all other readers jump to the parts of the document that most interest them.

- A detailed introduction provides needed context for external readers who may not be familiar with the project, your team, and even your company.

- A structure of independently sensical sections, each topped by a heading and perhaps subdivided into subsections with their own headings, make it possible for a variety of readers to navigate the document in the way that best meets their needs. For example, people from accounting can quickly find the part of the report dealing with money and budgets and ignore the rest of the report if desired.

- Placing supplemental and supporting information in an appendix means that readers who need even more detail than the body of the report provides can find and examine that material easily while not bogging down

Genre conventions are powerful because they mean you don’t have to reinvent the wheel for every new communication situation. The writer can follow familiar patterns and feel confident that, in so doing, the reader will find the resulting document familiar and easy to use, even if writer and reader have never met or different readers have different needs.

A Potential Problem

So on the one hand we have the idea of rhetoric, which helps us consider what the conditions of success are in getting a desired response from our audience. On the other hand, we have common genres, the conventions of which guide us when navigating unfamiliar or complex rhetorical situations.

But what do we do if these two guiding principles don’t match up? What do you do if, say, the genre conventions tell you to construct a document in one way, but your own analysis of the rhetorical situation and the audience’s needs suggest you should construct the document in a different way?

Do you follow the genre conventions, regardless of audience needs? Or do you put your audience’s needs first, even if it means breaking the “rules” of the genre you are writing in?

This question brings us to the thesis of this article, what I will call the Golden Rule of Professional Communication:

Always act in the best interest of the audience.

In other words, the genre conventions should take a back seat if you are ever forced to choose. And it makes sense—we call them genre “conventions,” not genre “rules” after all. They aren’t fundamental laws of the universe that were discovered by scientists but are instead social constructions—patterns that developed over time and with repeated use and that evolve, responding to changes in culture and need. The genre conventions of writing a business letter in 1920 aren’t the same as the ones in 2020.°

Subverting Genre

When you think about it, subverting genre is something you see quite often, and it can be quite powerful. Let’s go back to film, for example. While genre conventions do give us broad strokes by which to categorize movies, plenty of movies fall between the cracks.

Image via Wikipedia

One example is the 1984 classic Ghostbusters. It’s not exactly a horror movie, and it’s not exactly a comedy—it has elements of both (with some action and sci-fi thrown in too). And when you think about it, it only really works by combining the genres in the way it does. If the makers had set out to make a simple horror movie, they would have failed, and if they’d only had comedy in mind, the movie wouldn’t work. I like to imagine the film’s writers sitting down at the beginning of the project, analyzing the rhetorical situation. They knew the desired response they wanted to get was to entertain the audience in a unique way, and they thought about an all-ages audience that enjoyed both laughs and screams in equal measure. Refusing to be boxed into a single genre, they followed the Golden Rule and created a classic.°

Professional writing is very similar. In most situations, you’ll find that the genre conventions will serve you well, but occasionally, something specific about the message you are sending or the audience who will receive it will mean that you need to break with those conventions in order to succeed.

For example, most resumes are pretty buttoned-up documents—black text on a white background, conservative typefaces, etc.. But if you are a graphic designer applying for a job that will directly use your document design expertise, the Golden Rule might lead you to do something more adventurous in order to help your audience better judge your skills.

Three Goals for Professional Writers

This article has presented some big ideas that may sound simple but, in practice, can be quite tricky to employ—which is why you are probably reading this in the context of an entire college course devoted to the topic. Let me break it down for you then. The three qualities that make a professional communicator an expert at what they do are these:

- Rhetoric: They consistently and correctly anticipate the conditions of success behind any rhetorical situation.

- Genre: They master the genre conventions used in professional communication.

- Golden Rule: They know when to use genre conventions to navigate a rhetorical situation and when to break with genre conventions to better serve their reader.

As you learn about the specifics of professional communication, either in a college course or on the job, keep these big ideas in mind and weigh what you learn against them. Doing so will help you grow in confidence as you develop your professional communication skills.