You've probably noticed that, despite the total ubiquity of double spacing, 12-pt. Times New Roman font, and one-inch margins on every document you produce for school, you don't tend to see that stuff much in the real world. Out there is a typesetter's wild west—a wilderness of single spacing, of sexier fonts, of…well, the one-inch margins are pretty standard even there too.

So how will you know how to format documents in the real world once there are no teachers breathing down your neck? This article will lay out the basics for you. As it turns out, there's quite a bit more structure than first appears.

Here's everything we'll cover:

Why Should I Care about Formatting?

Okay, first off, let's be clear: There isn't really such a thing as "business formatting." At least, there are no absolute laws one must follow. These things aren't inscribed in the US Constitution or anything.° They're conventions, traditional ways of doing things that have been established by common use over a long time.

Because conventions are passed down from way back and tend to be so widespread, they can seem as deliberate and important as laws, and certainly as unbreakable. But they are not necessarily so. Think about how you bathe or shower—do you wash your hair first or your body? Chances are, you do one or the other first every time and have done so since forever. You probably do whatever your parent or guardian did when bathing you when you were young. And why did they do it in that order? Probably because that's what their parent or guardian did. There's no law that says you have to do hair before body or body before hair, and there's no inherent reason that makes one approach better than the other. It's a convention, not a law.

When we understand the conventions governing a space—whether they be those that govern document formatting or, as I mentioned at the top of the article, how one dresses—we empower ourselves to choose how others see us, either by adhering to the conventions or by deliberately skirting them.

Let's explore how understanding conventions can help you navigate two key elements of professional relationships: trust and convenience.

Trust

In business, trust is everything. The reason lawyers and contracts get involved so often is that trust is often scarce. The reason verbal agreements and handshakes can be as binding as a contract witnessed by a lawyer is that trust, when it exists, is, well, trusted.

Imagine for a second that you've saved up tens of thousands of dollars, borrowed hundreds of thousands more from family, and taken out a loan for over a million from a bank, all to set up a new business. You know that your idea is good, that it has the potential to bring in enough money to pay back all those loans and make a heap of money on top of that. But, in order to get your product to customers and make that money, you need to hire an accounting and supply chain management firm that can help get the product where it needs to go.

You visit three firms in order to choose which one to hire:

- Company One is a national corporation that has been in business for 80 years. They have a regional headquarters in a gleaming office downtown where you are greeted by name by an attractive, well-dressed administrative assistant, who ushers you into a fancy conference room with tall leather chairs. Waiting for you there is the regional manager, who heartily welcomes you with a handshake and offers you a seat. The assistant asks if you want an espresso, cappuccino, tea? You are introduced to the heads of the departments that will help handle your account, and each gives a well-polished but short presentation on what they can do and why they can be trusted to do the work well.

- Company Two is a local outfit that's been in business for 15 years. Their offices are in an industrial part of town where many of their clients are located, and the sound of large trucks entering and leaving nearby warehouses sometimes make conversation difficult. You are welcomed by an attractive, well-dressed receptionist, who radios to the boss that you've arrived and leads you to the conference room, which is functional if not fancy. The boss arrives, clearly having come from one of the warehouses, in professional attire but no jacket, hands freshly washed but still damp, sleeves rolled up. After introductions and a short presentation, you are taken on a tour of the office, where you meet many of the polo-and-khakis clad department heads who will be managing your account.

- Company Three is a small firm that was started five years ago as a spinoff of a successful local shipping business, so their "offices" are in the shipping business's warehouse. The boss, attired in shabby flannel and denim, meets you at a nearby coffee shop, buys you a coffee, gets grease on your hand when shaking it. You walk together to the fence of the warehouse facility, where the sister company's trucks are pointed out and the business explained over the sounds of nearby construction. While you're talking, someone sketchy approaches the boss, they have a short interchange, and the boss counts out and hands over a substantial stack of 20s.

Let's say that each company offers essentially the same service for the same price.

You have over a million dollars of other people's money in your pocket, not to mention your own life savings. Which company do you trust with your business? How do you determine who to trust?

Of course you would look more into the reputation and history of the business before making your decision, as these things are better predictors of future behavior than what the employees were wearing and how fancy their offices were. But, if we're being honest, we know the shallower things affect our decisions too—humans are impressed by professional dress and surroundings, are softened by good coffee and courtesy.

Those who understand and are masters of such conventions are better prepared to close the deal. Company Two didn't have to use a radio to communicate, nor did Company Three's boss have to wear flannel—these could be deliberate choices meant to evoke something more than just trust, or to invoke trust in a different way.

Formatting your business documents according to the conventions—or deliberately deciding not to—can likewise help you establish trust of various kinds and to varying degrees.

Convenience

Now let's discuss formatting more directly. Imagine you're a busy professional who receives hundreds of letters a week asking for all sorts of things: jobs, contracts, speeches, mentorships, referrals, introductions, lunches, etc.

When those letters follow the conventions of business formatting, your life is made easier. You don't have to flip to the end of the letter to figure out who is writing, because the sender's name and address is at the top of page one. You don't have to find the postmark on the envelope to discover when the letter was sent, because the date is right there under the sender's address where you expect it to be. You don't have to wonder what the person is asking for because they state it clearly in paragraph one.

You're not going to say yes to all of these requests, of course, but your reason for saying no won't be that they made your life more difficult in the asking.

Some letters arrive with a formatting all their own. They include all the same parts, but they are in a unique arrangement. They are in a difficult-to-read font, or are handwritten, or are in such a small font size that your aging eyes can't decipher it. You have to do more flipping of pages, more hunting through the lines to find what you need to make a decision.

You're not going to say no to all of these requests, of course, but you might be more inclined to say no—you might even misunderstand what is being asked—because of how inconvenient the asking is. If you're truly busy you might toss the letter aside without ever reading it at all.

Now imagine the worst-case scenario: A large stack of letters that need answering are knocked off your desk and scatter hopelessly all around your office, the page-ones separated from their respective page-twos and -threes and so on. Those letters that are written in standard business formatting can easily be reconstructed, since the sender's address on page one corresponds to the signature on page two. Longer letters that use a header on subsequent pages—with a name, date, and page number—are no problem, even if they all use the exact same paper, font, and margins. But those format-less letters might be beyond repair, and even if you could reunite their pages, do you even want to bother?

Remember, the very act of writing to someone is putting yourself in their debt. The reader doesn't exist to serve you, doesn't owe you anything. They are the one doing you a favor by reading your words, so you must serve the reader at all costs. Business formatting is simple way of performing that service, by ensuring convenience.

An Important Disclaimer

Remember, what we're talking about are conventions, not laws. There is no absolute standard for business formatting, and variations within reason are common and expected. In fact, if you browse enough books and websites, you'll find almost every possible variation, each one presented as the absolute law. But they can't all be right, right?

Contrary to those prescriptive resources, I'm making no claim that what is presented here is universally correct. But I will give you something more valuable than such empty assurances: reasons.

Block Formatting

Block formatting is the default for all business documents. Unless you have a good reason not to for a specific document or situation, you should always use block formatting.

Block formatting is so named because the paragraphs appear to be solid, rectangular blocks of text on the page. This is achieved by doing three things:

- The text is single-spaced.

- There is a blank line between paragraphs.

- The first line of each paragraph is not indented.

How To Achieve Block Formatting

Someday I'll write up my own explanation, but for now, you can't do better than Butterick's Practical Typography. Check out its pages for line spacing and space between paragraphs.

Why Do It That Way?

Double-spacing is common because, back when teachers and editors wrote directly on paper drafts, they needed space between lines to write. Even though teachers, at least at the college level, do less and less actual writing on paper drafts, the tradition persists. However, in the professional world, the reader of your letters, memos, and emails are not typically editing your work and giving you feedback, so double-spacing is, to be blunt, a waste of space and paper. So we single-space.

There isn't as elegant an explanation for why we use a blank line between paragraphs rather than indenting their first lines. There is, however, a good reason we don't do both:

First-line indents and space between paragraphs have the same relationship as belts and suspenders. You only need one to get the job done. Using both is a mistake. If you use a first-line indent on a paragraph, don’t use space between. And vice versa.

—Matthew Butterick, Butterick's Practical Typography

With double-spaced text, indenting the first line is the better way to signal a new paragraph, since an extra line of spacing will disappear amongst all the spaced lines. With single-spaced text, opting for the space between paragraphs is just prettier, resulting in the blocks of text that give block formatting its name.

One more thing: It's almost always best to use left-alignment on your paragraphs, not "justified" alignment. While having the text line up with both the left and right margins, rather than just the left, might seem more formal and more "blockish," in reality it usually looks slapdash and unpolished unless it is professionally typeset that way.

Letters

Formal business letters are documents you generally send to people outside your organization, or, if they go within your organization, they are to someone quite removed from you or are used for a particularly formal situation.°

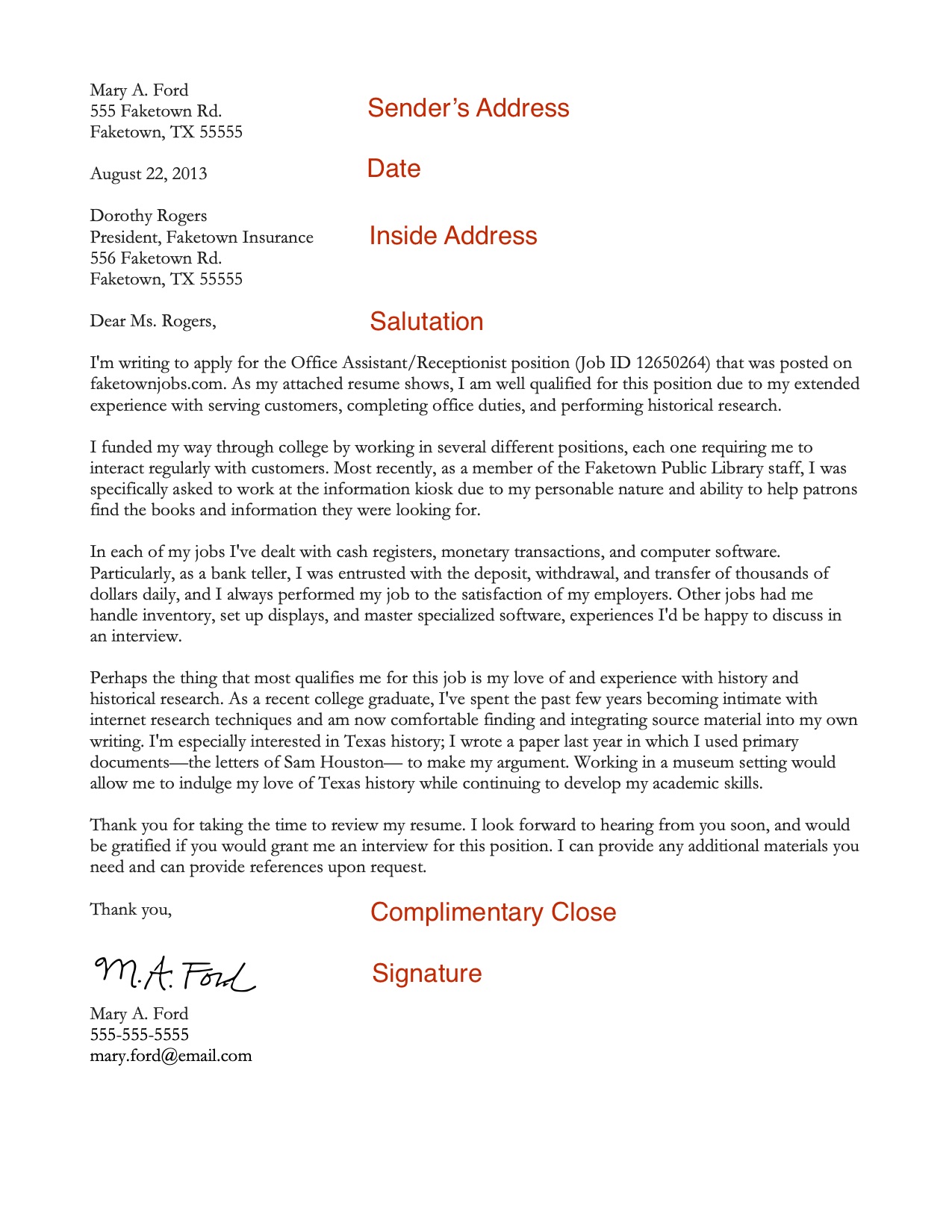

Here's what a formal letter typically looks like:

Let's discuss each component part.

Sender's Address

Your name, title, and contact information should come first on the page and should be single-spaced as a block of text (you'll need to zero out the spacing after each paragraph if your word processor adds spacing as a default). It should be aligned with the left margin.

Why We Do It: It's inconvenient to make your reader flop to the end of the letter to find out who you are. If you met someone face to face for a business meeting, the first thing you would do it introduce yourself, so that's what you do in a letter.

Acceptable Variations: It's rare, but I've seen letters that right-align or even center the sender's address and the date. I don't recommend it since I can't think of any reason to do it and it isn't common.

If you are using paper with letterhead on it, and the letterhead includes your name and contact info, you can ditch the sender's address entirely. If the letterhead includes just your business's name and contact info, you can keep the sender's address or add your personal contact info below your signature at the end of the letter.

Date

After a blank line, include the date you wrote the letter.

Why We Do It: Because the date something was written is generally important to most readers in most situations. Also, if you have multiple exchanges with someone, this becomes an easy way to distinguish letters: "In your letter dated 21 August 2020 you wrote that…"

Acceptable Variations: The format you use for the date is up to you. The most traditional approaches are month day, year and day month year.° You can also do month/day/year using numbers only, but note that many countries use day/month/year instead, which can lead to spectacular and/or hilarious miscommunications.

It's okay to abbreviate the month name, but why would you? You don't need to save space here, and the spelled out name looks more formal and classy.

Inside Address

After another blank line, give the name, title, and contact information of the person to whom you are sending the letter, as single-spaced as a block of text.

Why We Do It: For one, it's a chance to schmooze the recipient by showing you did enough homework to know who they are and what fancy titles and degrees they have, similar to how you might do in a face-to-face meeting. But more importantly, this is probably a holdover from the days when an administrative assistant would open the boss's mail and ditch the envelopes before passing them along. Since there's a chance that the letter—devoid of the envelope and its address—could be mixed up, dropped, or otherwise misdirected, including the inside address here was a safe move.

Acceptable Variations: If you don't know the exact recipient's name and can't find out through basic research, it's okay to address the letter to a department (such as "Human Resources"). If the letter will be electronically transmitted, such as a PDF attached to an email, it's okay to not include a full street address for the recipient, though it might look sloppy.

Salutation

After another blank line, address the person to whom you are speaking, as in "Dear Dr. Grover." Unless you're on a first name-basis with the recipient, it's best to use their title and last name.

Why We Do It: Because that's how letters typically begin.

Acceptable Variations: Some people find "Dear" to be too familiar; it's okay to just state the name. You can even eliminate this line altogether, especially if you're writing to a group.

Some resources say to use a comma at the end of this line, some a colon, and some nothing.° I think a comma looks best and is most common, but all are okay.

Body

Next comes the body of your email in block formatting. The most important thing here is that you state your reason for writing or your request in the first paragraph.

Why We Do It: You're already in your reader's debt by asking them to read your letter—don't make it worse by making them to wait to discover what your purpose in writing is.

Acceptable Variations: For longer letters, feel free to use headings to break up the text into chunks, making it easier for the reader to navigate quickly. You might also use bulleted or numbered lists, figures, tables, etc., as appropriate.

Complimentary Close

At the end of the body, leave another blank space, and write "Sincerely," or "Yours Truly," or some other complimentary close.

Why We Do It: It's polite, and it's one last chance to schmooze a bit.

Acceptable Variations: You can use any close you want, but its formality should appropriate for your relationship with the reader and the situation in which you're writing. "Sincerely" is always safe; "Yours in Christ" or "Say hi to your mom for me" much less so.

Signature

Leave enough blank space that you can physically sign your name on the paper once printed (four lines is a common instruction), and then type your name.

Why We Do It: Because that's how letters always end.

Acceptable Variations: You can include additional information on subsequent lines such as your title, position, or company, but if you've already included those at the top of the letter, you risk coming off as snooty.° On the other hand, including it at the top and then not including it at the bottom implies that, in the act of reading the letter, the reader has now become more intimate with you, that you are inviting them into your no-title circle of friends.

I personally like using my physical address at the top of the letter and then including my phone and email under my signature line, as this further implies that we've become familiar. At the top of the letter, when you didn't know me, we were all business, but here at the bottom, we're friends, so feel free to call me directly.

If the letter will be electronically transmitted, such as a PDF attached to an email, it's okay to just type your name and not sign, but it always looks better to include an electronic signature if you can. Many PDF programs allow you to create a signature for yourself and then attach it to any document; it's worth the trouble to set up once.

Additional Elements

Enclosures: If the envelope includes documents in addition to the letter, then under your signature, include a line that says "Enclosures" or "Encl." and a list of what those things are, like this:

Enclosure: Resumé

This ensures that, if the pages get mixed up, dropped, or misplaced, the original contents of the envelope can all be reunited.

Subsequent Page Headers: If your letter goes onto a second page or more, include a header on those pages that includes your name, the date, and the page number. These three things will allow the pages of your letter to be reunited, even if a whole stack of letters—all from you, all formatted identically otherwise—were tossed in the air and blown halfway across town.

Subject Line: It's possible to include a subject line in a letter, much the way that an email always includes one. These are typically inserted between the salutation and the body of the letter, in all caps, like this:

Dear Dr. Grover:

REQUEST TO ACT AS MY MENTOR

I'm writing to formally ask if you would be willing to…

Might this be useful for your reader? Sure. Does it look like you're shouting at them? Definitely.

Memos

Whereas letters are usually sent outside your organization, memos are typically distributed within the organization. It's also common for memos to have multiple recipients, such as being sent to an entire department.

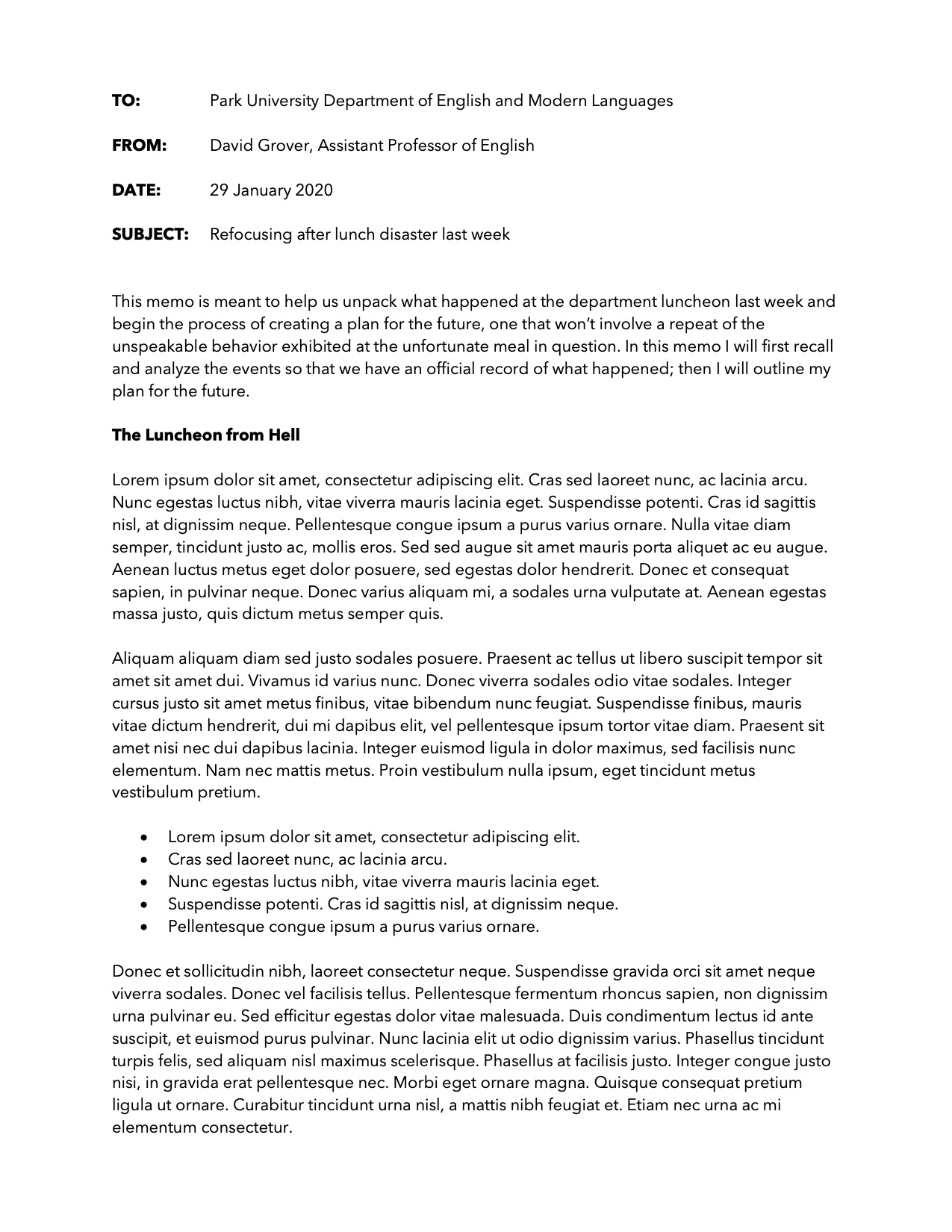

Here's what a formal memo typically looks like:

Let's discuss each component part.

Heading

The heading is the thing that makes a memo a memo, and it always specifies these four things: the sender, the recipient, the date, and the subject.

Why We Do It: Because this is what the reader needs to know to understand the memo's context.

Acceptable Variations: You'll see a lot of variation if you look around:

- The order of these lines might be switched up.

- The SUBJECT line could be called RE (as in "reason").

- The date can be given in any format.

- The lines can be single- or double-spaced.

- TO, FROM, etc. can be in all caps or not.

- Bold text can be used (as in the example above) or not.

- The entries for each category can be tabbed over and lined up (as in the example above) or not.

- Additional lines (like CC or PRIORITY) can be added as needed.

Body

Next comes the body of your memo in block formatting. The most important thing here is that you state your reason for writing in the first paragraph. Specific types of memos might have specific body requirements.

Why We Do It: You're already in your reader's debt by asking them to read your memo—don't make it worse by making them to wait to discover what your purpose in writing is.

Acceptable Variations: For longer memo, feel free to use headings to break up the text into chunks, making it easier for the reader to navigate quickly. You might also use bulleted or numbered lists, figures, tables, etc., as appropriate.

Additional Elements

Complimentary Close and Signature: These are not typical on a memo, as it is not a letter, but you will see it, especially if the writer wants to make the document seem personal but a letter format isn't appropriate. For example, a memo containing bad news from the company president might be signed to humanize the delivery.

Subsequent Page Headers: If your memo goes onto a second page or more, you could include a header on those pages that includes some combination of your name, the date, an abbreviated form of the subject, and/or the page number. All of those are optional except the page number, which is simple courtesy.

The Word MEMO: Many of the samples and templates you'll find floating around the web include MEMO or Memorandum in huge letters at the top or even sideways along one margin. Is this necessary? Absolutely not. Is it wrong? Um…I guess not? It seems a bit like writing t-shirt on your t-shirt or house on your house.

Letterhead: Memos can be printed on letterhead. Just be sure the heading is placed so that it doesn't overlap the letterhead.

Emails

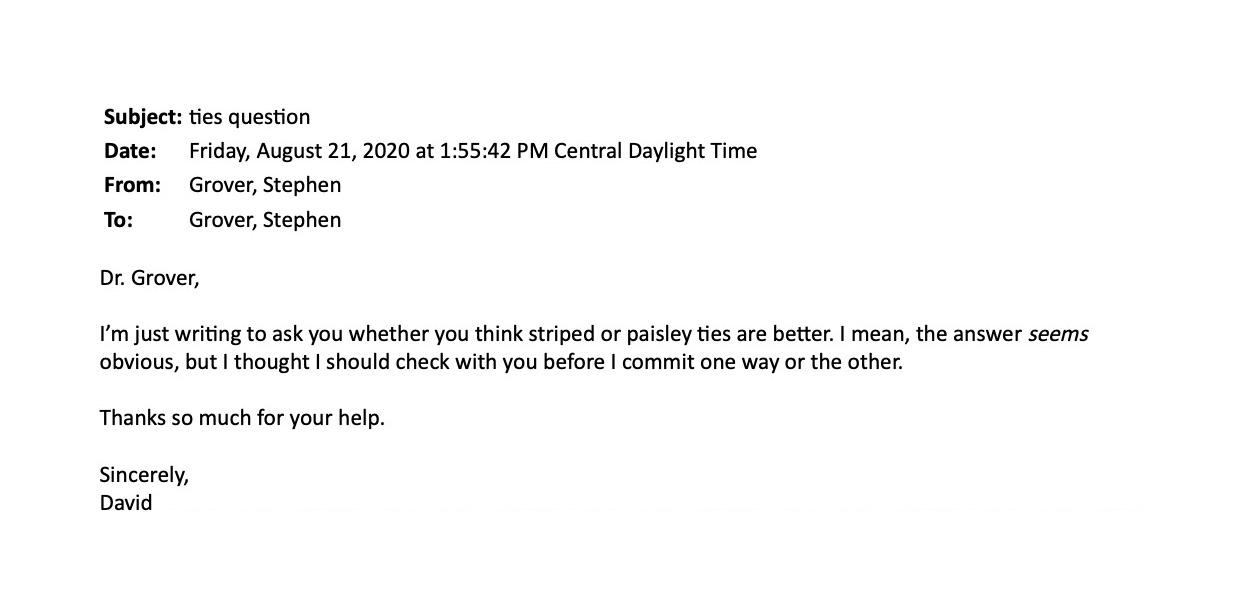

Here's what a typical email looks like:

Something you should notice is that, though the name email implies an email would be nothing but an electronic letter, in actuality it has more in common with a memo. Notice how the heading is similar to a that of a memo?

Here's the scoop: Both business letters and memos can be sent as emails. When you send a business letter as an email, you typically drop the sender's address, date, and inside address, since those things are already hard-coded into the email.° When you send a memo as an email, there's no need for a separate heading, since those things are already part of the email. Everything else can be done the same.

Conclusion

Remember, all the things presented here are conventions, not rules. Understanding them gives you power because you can decide to follow or flout the traditions to better gain your purpose. You can manage the level of formality or familiarity in an exchange, much as you do by managing your wardrobe.