Any publisher has what is called a “house style.” The house style dictates, for example, how sources are to be cited in a text—whether as footnotes, endnotes, or in-text citations, and whether authors’ complete names are given in a citation or just a first initial and last name. Style determines how words, especially technical terms, are to be used, capitalized, abbreviated, and more. It dictates whether one writes a number as a word, as in seventeen, or as a numeral, as in 17. Style can even define how many levels of headings are allowed in a document and how they are formatted.

So you might be wondering: How is a house style created? Who makes these decisions, and how are they communicated amongst the editorial staff? How are they revised?

If you’ve ever seen the Chicago Manual of Style, now in its 17th edition and clocking in at over 1000 pages,° your wonder might turn to stupefaction: How can every publisher develop their own in-house style if the Chicago Manual took 17 editions to do so and a thousand pages to explain?

Look at this glorious hunk.

Image via Wikipedia

Don’t worry—an in-house style isn’t as complicated as it sounds, and it doesn’t generally require writing an entire book. And if you get hired as an editor, learning a house style doesn’t require memorizing an entire new book.

Let me illustrate by sharing my experience of learning the house style at my first editing job. Though the house style I'll describe is maybe a bit more elaborate than average, you'll find that many publishing houses and departments take a similar approach.

House Style at the RSC

As I explained in “How I Accidentally Became an Editor,” I got my first editing job as a senior at Brigham Young University. I worked for the Religious Studies Center, which is the publishing arm of the university’s religion department.

The RSC, at that time, published an academic journal, scholarly books, and nonfiction books for a popular audience, all on religious and historical topics. It was a relatively small organization. A religious scholar from the university faculty served as the director of the RSC, and an administrative assistant handled office duties. The only other full-time employee was the executive editor, who had many years’ experience in the editing profession and provided guidance to the editorial team, which consisted of half a dozen part-time student editors (like me) as well as a few typesetters, graphic designers, and researchers.°

The executive editor had created the house style used by the RSC, but not by writing a book to guide our decisions. Instead, we used three resources, each nested within the previous one, creating a layered approach to defining our style.

Layer One: A Broad Foundation

The foundational layer of our house style was—wait for it—the Chicago Manual of Style.

I mean, why write a book when the book has already been written for you? The Chicago Manual has long been a standard of the publishing industry, especially nonfiction publishing, and it covers more than our poor executive editor could ever have defined on his own.

Just looking at the table of contents reveals how much useful ground the manual covers. For example, here are the chapters and major sections for Part I of the manual:°

Part I: The Publishing Process

- Books and Manuals

- Overview

- The Parts of a Book

- The Parts of a Journal

- Considerations for Electronic Formats

- Manuscript Preparation, Manuscript Editing, and Proofreading

- Overview and Process Outline

- Manuscript Preparation Guidelines for Authors

- Manuscript Editing

- Proofreading

- Illustrations and Tables

- Overview

- Illustrations

- Tables

- Rights, Permissions, and Copyright Administration

- Overview

- Copyright Law and the Licensing of Rights

- The Publishing Agreement

- Subsidiary Rights and Permissions

- The Author's Responsibilities

As you can see, not only does this part of the book explain how books and journals are arranged—giving sensible guidelines for what to include on, say, the copyright page or the title page—it also defines a standard editorial process, explains how best to include illustrations and tables in a text, and more.

Part II is even more useful:

Part II: Style and Usage

- Grammar and Usage

- Grammar

- Syntax

- Word Usage

- Punctuation

- Overview

- Punctuation in Relation to Surrounding Text

- Periods

- Commas

- Semicolons

- Colons

- Question Marks

- Exclamation Points

- Hyphens and Dashes

- Parentheses

- Brackets and Braces

- Slashes

- Quotation Marks

- Apostrophes

- Spaces

- Multiple Punctuation Marks

- Lists and Outline Style

- Spelling, Distinctive Treatment of Words, and Compounds

- Overview

- Plurals

- Possessives

- Contractions and Interjections

- "A" and "An"

- Ligatures

- Word Division

- Italics, Capitals, and Quotation Marks

- Compounds and Hyphenation

- Names, Terms, and Titles of Works

- Overview

- Personal Names

- Titles and Offices

- Epithets, Kinship Names, and Personifications

- Ethnic, Socioeconomic, and Other Groups

- Names of Places

- Works Derived from Proper Names

- Names of Organizations

- Historical and Cultural Terms

- Calendar and Time Designations

- Religious Names and Terms

- Military Terms

- Names of Ships and Other Vehicles

- Scientific Terminology

- Brand Names and Trademarks

- Software and Devices

- Titles of Works

- Numbers

- Overview

- Numerals versus Words

- Plurals and Punctuation of Numbers

- Inclusive Numbers

- Roman Numerals

- Abbreviations

- Overview

- Names and Titles

- Geographical Terms

- Designations of Time

- Scholarly Abbreviations

- Biblical Abbreviations

- Technology and Science

- Business and Commerce

- Languages Other than English

- Overview

- General Principles

- Languages Using the Latin Alphabet

- Languages Usually Transliterated (or Romanized)

- Classical Greek

- Old English and Middle English

- American Sign Language (ASL)

- Mathematics in Type

- Overview

- Style of Mathematical Expressions

- Preparation and Editing of Paper Manuscripts

- Quotations and Dialogue

- Overview

- Permissible Changes to Quotations

- Quotations in Relation to Text

- Quotation Marks

- Speech, Dialogue, and Conversation

- Drama, Discussions and Interviews, and Field Notes

- Ellipses

- Interpolations and Clarifications

- Attributing Quotations in Text

It’s hard to imagine having a question about grammar, punctuation, spelling, or capitalization that isn’t covered somewhere in these chapters. Indeed, in my work at the RSC, probably 98% of the questions that came up while editing were answered by a quick reference to Chicago. I spent so much time consulting it, in fact, that I was soon referring to it by numbered subheading. A fellow editor would say something like, “Do I capitalize and italicize the “the” in “the New York Times?” and I would shout out, “8.170!” having looked up that same question enough time to know exactly where to look.°

Part III of Chicago was even more useful still, as this is the section of the book that describes how to cite sources and create bibliographies.

Part III: Source Citations and Indexes

- Notes and Bibliography

- Source Citations: An Overview

- Basic Format, with Examples and Variations

- Notes

- Bibliographies

- Author's Name

- Title of Work

- Books

- Periodicals

- Websites, Blogs, and Social Media

- Interviews and Personal Communications

- Papers, Contracts, and Reports

- Manuscript Collections

- Special Types of References

- Audiovisual Recordings and Other Multimedia

- Legal and Public Documents

- Author-Date References

- Overview

- Basic Format, with Examples and Variations

- Reference Lists and Text Citations

- Author-Date References: Special Cases

- Indexes

- Overview

- Components of an Index

- General Principles for Indexing

- Indexing Proper Names and Variants

- Indexing Title of Publications and Other Works

- Alphabetizing

- Punctuating Indexes: A Summary

- The Mechanics of Indexing

- Editing an Index Compiled by Someone Else

- Typographical Considerations for Indexes

- Examples of Indexes

One thing you might notice here is that Chicago is probably more liberal in this respect than you might be used to. Whereas MLA and APA styles more or less demand the use of parenthetical in-text citations as the form of documentation—Chicago calls this the “Author-Date” style and covers it in chapter 15—Chicago allows one to either use parenthetical citations or footnotes/endnotes (which it calls a "Notes and Bibliography" style, contained in chapter 14).

At the RSC, we typically used footnotes or endnotes for our publications, since that style best served our readers’ needs and preferences. I became very well versed in this section of the book too, able to recite the numbered heading for many of the rules as I used them, and consulted the book, so often.

Layer 2: More Specific to the Topic

As comprehensive as Chicago is, it didn’t answer every question or address every issue that came up. The RSC is a unit within Brigham Young University, a private university owned and operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Church represents a major worldwide religious and cultural movement with millions of members, a complex administrative structure, its own books of scripture, an extensive history, and a vibrant scholarly community.

As you might expect, the Church does a fair amount of publishing of its own, both of internal-use materials like magazines and instruction manuals but also of press releases and other public-facing documents. For this reason, the Church has developed its own style guide to promote consistency, especially of terms and usages that are unique to its culture and scholarship.°

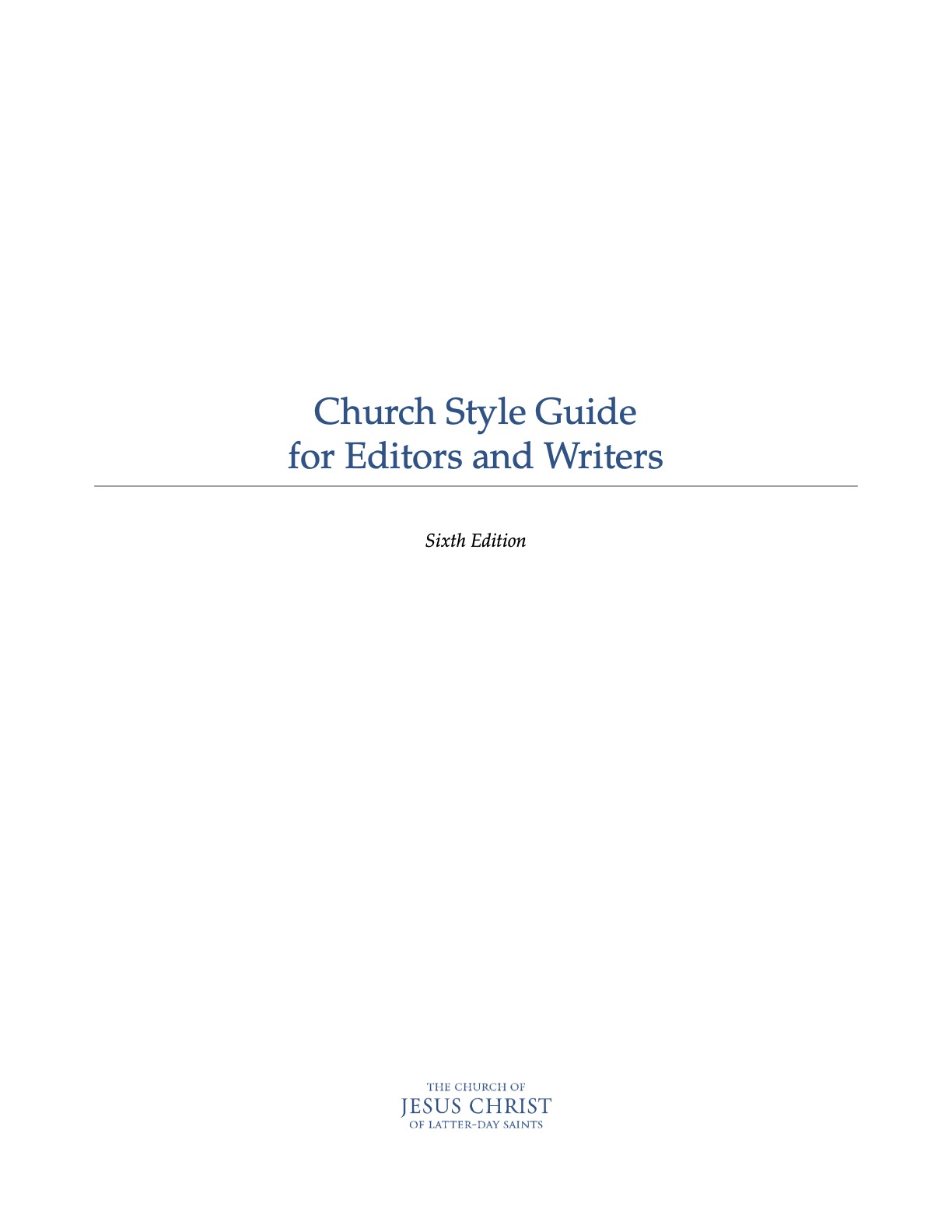

This style guide is called, perhaps unoriginally, the Church Style Guide for Editors and Writers. Currently in its sixth edition, it’s about 75 pages long.

As at the RSC, the Church does not intend this slim booklet to do everything on its own; in fact, its preface notes the following:

Because Church publications generally follow the principles suggested in the 17th edition of The Chicago Manual of Style (herein referred to as Chicago), this guide is concerned primarily with matters in which Church style differs from that of Chicago or is more specific than Chicago’s suggestions.

So what are these things that are “more specific” than Chicago? Well, as you can see from the table of contents, the whole of chapter 3 is devoted to how official letters and notices from Church headquarters are to be formatted.°

Of course, chapter 3 wasn’t useful to my editing at the RSC. I spent my time elsewhere. For example, chapter 7, called “Spelling and Distinctive Treatment of Words,” and chapter 8, “Names and Terms,” include several long lists of Church-specific jargon with information about how to spell, capitalize, and hyphenate these correctly. Since the academic work we published at the RSC frequently made mention of Church-specific terms like administrative titles (e.g., “bishop,” “stake president,” “general authority”), organizational units (“bishopric” and “elders quorum”), and meetings (“general Relief Society meeting” and “ward council meeting”), and since Chicago of course does not include specific sections on such terms, I referenced these lists a lot.

Chapter 10, “Abbreviations,” was crucial because Church style differed from and went beyond what Chicago specified, especially with scriptural names. For example, when referencing books in the Bible, Chicago gives two sets of abbreviations: longer, traditional abbreviations, which include periods, and shorter forms that include no periods. The Gospel of Matthew, for instance, can be abbreviated as “Matt.” for the longer form or as “Mt” for the shorter form.

The Church Style Guide, however, specified that only “Matt.” should be used. Chicago abbreviates Thessalonians as “Thess.” but the Church guide specified “Thes.” For Nahum, which Chicago gives as “Nah.”, the Church didn’t allow an abbreviation at all.

More than this, though, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints teaches scriptures beyond the Bible’s Old and New Testaments. The most famous, of course, is the Book of Mormon, which includes 15 “books,” similar to those found in the Bible, and each with its own abbreviation, none of which appear in Chicago at all.

Did you notice how I slipped into the past tense there? The Church's prescribed abbreviations are now a thing of the past. When I edited for the RSC, back in the days of the Style Guide's 3rd edition, abbreviations of books of scripture were allowed. In the current 6th edition, chapter 10 is now a single page and states, "In running text and notes, do not abbreviate references to books of the Bible [and] the Book of Mormon…."°

Layer 3: Hyper-Specificity

Between Chicago and the Church Style Guide, 99.9% of our questions about style at the RSC were answered. But still, the RSC’s mission is primarily scholarly, tied as it is to a university, which means that we did encounter situations where neither of those resources was specific enough or their advice was otherwise inappropriate to what we were publishing and its audience.

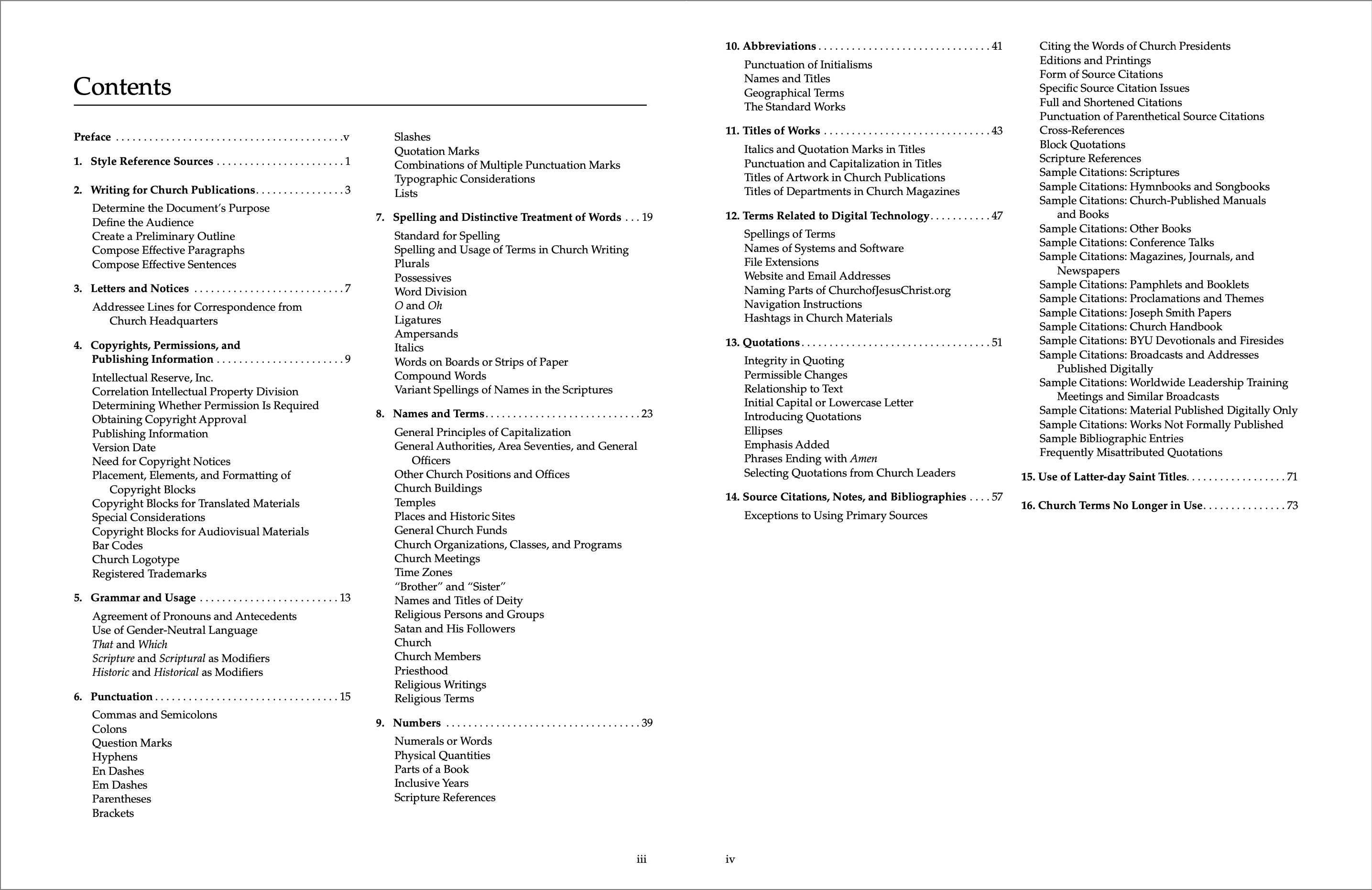

For these instances, we had the "Religious Studies Center Style Guide."

Notice I didn’t put this title in italics. That’s because the "RSC Style Guide" wasn’t really a formal publication at all—it was just a Word doc of half a dozen pages that existed on the executive editor’s computer and of which a few printouts could be found around the office. Frankly, it feels weird even putting quotation marks around the title of something so short.°

In my time at the RSC, the style guide was mostly an internal document listing those few exceptions to the other style guides that mattered to our work, and it had been compiled as such issues came up. Since my time, the document has been expanded and formalized a bit (though it still proudly wears its basic Word formatting), and it has become a document instructing authors who hope to publish through the RSC on how to properly prepare their manuscripts. It still clocks in at just 13 pages, and it begins with a familiar note:

Authors who submit manuscripts for potential publication should generally follow the guidelines in The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017) and Church Style Guide for Editors and Writers, Sixth Edition (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2020). This style guide summarizes the main principles in the other style guides and lists a few exceptions to their guidelines.

So what are some of those exceptions? One involves citing the Bible. Since multiple translations and versions of the Bible exist, Chicago directs that the version being used should be specified on the first occurrence of a biblical reference. However, the Church more or less universally uses the King James Version of the Bible, so the RSC style guide specifies that one only need specific the version of the Bible being cited if it is not the King James Version, saying to spell out the version name on the first use and then abbreviate it in later entries, giving this example:

(Matthew 15:3 New International Version)

(Matthew 15:4 NIV)

The Church's Style Guide doesn’t even mention this possibility, probably because things produced directly by the Church will naturally always default to the Church-sanctioned version. Scholars, however, regularly draw from multiple versions of the Bible in their work, so this necessitated and entry in the RSC guide.

Another example of something more specific in the RSC guide is that, in the section on citing sources, there’s an entire subsection devoted to guidelines on citing “Unpublished Materials” that are commonly used in historical scholarship commonly published by the RSC. There are extensive examples of citations for things that can be found in the Church History Library in Salt Lake City as well as the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, which is a part of the university library on BYU campus.

You could probably use Chicago to figure out how to cite sources like these in a consistent, understandable way, but if RSC editors only had Chicago to draw on, they’d find themselves having to surf the index, reading between the lines of sections, and scrabbling together the method from scratch each time. Likely the results wouldn’t be consistent each time. By writing an RSC-specific policy for citing these common-to-the-RSC sources, we saved ourselves a lot of time and promoted greater consistency.

Conclusion

Alright, I get how this can seem overwhelming, and my first month on the job it did seem like a lot. There's a steep learning curve to figuring out how three separate style guides nest together to create one house style.

But here's one thing to keep in mind: Chicago forms the basis of many (if not most) professional house styles. Once I learned Chicago, which honestly did not take long at all, given how often I had my nose in it tracking down one arcane rule or another, I could've easily transitioned into employment with another publisher, learning their house style in no time.

To use a metaphor: Going from one house style to another isn't like learning to ride a bike and then learning how to fly a plane. It's more like learning how to ride a mountain bike and then transitioning to a racing bike. They're all bikes, really, when you get down to it.